On this page: Canonical hours // Celebrating the hours // Mass and Communion // Liturgical texts // Music

These screens use images, anecdotes and also music to provide an insight into monastic devotion in the church. Information about the appearance of the church – the layout and decoration – can be found in the Cistercian church.

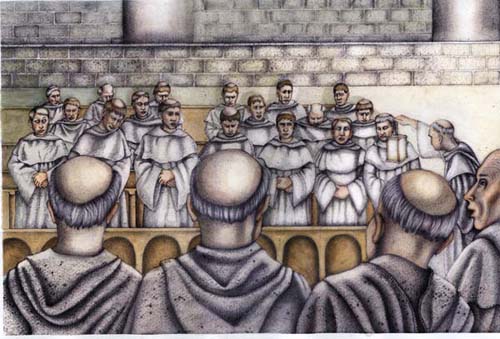

The monks’ day was structured around the eight Offices, known as the Canonical Hours, which they celebrated in their choir. The monks also entered the church to attend a daily Mass, to receive Communion, and for special occasions such as dedication ceremonies, funerals and the unction of the sick. A large proportion of the monk’s day was therefore spent in church, and even part of the night for the community assembled in the choir stalls c. 2 am to celebrate the night office of Vigils.

Whereas the Black monks of Cluny celebrated up to 210 psalms a day, the Cistercians celebrated the psalmody of 150 psalms over the course of the week, as prescribed in the Rule of St Benedict.

[L. Lekai, The Cistercians: Ideals and Reality (Ohio, 1977), p. 248]

Simplicity and uniformity stood at the heart of Cistercian ideology. They considered complicated and lengthy services excessive, and also a potential cause of boredom and sloppiness. Quality, not quantity was the decisive factor, and devotions were therefore to be kept as simple as possible. The Cistercians reduced the number of masses and processions, as well as the length of the psalmody, and ordered that the monks should sing devoutly, like men, without shrills, trills or musical instruments. To ensure that the form of worship was the same in every Cistercian abbey, in other words, that there was uniformity of practice, the General Chapter ordered that the same prescribed liturgical texts should be used by each community. This meant that if a Cistercian monk visited another abbey of the Order he would be able to take his place with the host community and follow the services there, just as if he were in his own abbey.

Canonical hours

The monks’ time was structured around eight services (Offices), known as the Canonical Hours, which they celebrated in their choir in the church. At harvest time, however, these were recited as the monks worked in the fields. Following the words of Psalm 119: 164 ‘Seven times a day have I given praise to thee’, and Psalm 119: 162‘At midnight I rose to give thanks to Thee’, there were seven daytime Hours [Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None(s), Vespers and Compline] and a night office known as Vigils (although this was generally celebrated at around 2 am rather than midnight.)

As the monastic day was determined by the rising and setting of the sun, the exact time of each Office varied over the course of the year. Whereas Prime was celebrated at c. 8 am in winter, it took place at c. 4 am in summer.

Each Office was led by the priest of the week (the hebdomadary) and began with the Lord’s Prayer, which was followed by hymns (sung from the hymnal), psalms (from the psalter) and canticles or chants (from the antiphoner). The time of Vigils was standardised from 1429 and the sacrist was to give the signal for this Hour at 2 am every morning, regardless of the time of year; however, Vigils was at 1 am on Sundays and feast days since the liturgy was longer on these days.

Preparation for the Divine Office’

Focus your eyes on one place in front of you to the best of your ability and as your human frailty allows. Wandering eyes are most harmful to the mind’s stability. To elicit humility, therefore, form a mental picture of the Lord as if he were lying in the manger in front of you. To feel compunction visualise him suspended on the Cross. Grieve and be thankful because of the nails, the thorns, the spittle and the gaping wound at his side.

[Stephen of Sawley, Mirror for Novices, ch. 3, p. 91].

All of the monks were required to attend every Hour although certain officials, such as the porter, were excused on account of their duties. Punctuality was important and anyone who arrived late had to kneel facing the altar at the presbytery step until the abbot signalled that he could return to choir, where he took the last place. Anyone who was late on a Sunday or a feast day was more severely punished or, at least, the punishment was more gruelling for the latecomer had to bow, stretch his hands until they touched the floor and remain in this position until the abbot signalled that he could join the others in the choir.(1)

The monks did not prostrate themselves to pray but remained upright and stood for the night office of Vigils, probably to make sure they kept awake. One of the monastic officials would keep an eye on the monks to make sure that nobody drifted off to sleep and shine his lantern in the face of anyone who looked as if he might nod off. A number of anecdotes recount tales of monks and lay-brothers who fell asleep during the Offices, particularly – and not surprisingly – at the night office of Vigils. These stories were intended as a warning to would-be sleepyheads of the seriousness – and potential repercussions – of dozing off in church. One such tale describes how a particular monk, who was notorious for falling asleep, had a rather rude awakening. The monk nodded off at Vigils and saw in his sleep a tall, misshapen man, holding a filthy wisp of straw, the kind used by grooms to rub down horses. The man leered at the monk, asked why he ‘son of the great Lady’ slept (an allusion to the fact that the Virgin was patron of the Cistercian Order), and then struck him over the face with the filthy straw. At this point the monk awoke, instinctively drew back his head from the blow and, much to the amusement of his fellow brethren, banged his head against the wall.(2)Another monk who was prone to doze off in church was rather less fortunate when he fell asleep at Vigils, for the image of the crucified Christ came down from the altar to waken him up, but struck him with such a blow upon the cheek that the poor monk died three days later.(3)

Celebrating the hours

It behoves men to sing with manly voices and not imitate the lasciviousness of minstrels by singing with shrill voices like women, or, in common parlance, falsetto. And, therefore, we have decreed that extremes in singing be avoided so that the singing may be redolent of seriousness and devotion be preserved.

[Institutes of the General Chapter, LXXV, in Waddell, Narrative and Legislative Texts, p. 489.]

The quality of worship was vital to the Cistercians. The monks were not to rush the psalms, slur or skip the words, and were to sing like men rather than shriek like women. Criticism was levelled at the Black Cluniac monks who took expensive liquorice cordials to help them reach the high notes when singing the Office. (4)

© Cistercians in Yorkshire

Aelred of Rievaulx was particularly scathing of musical embellishments, and censured the ‘swelling and swooping’ of voices, the ‘din of bellows and the humming of chimes’ which, he argued, made a mockery of worship; sound, he argued, was of secondary importance and should merely enhance the meaning.

Aelred of Rievaulx: The Mirror of Charity

Where, I ask, do all these organs in the church come from, all these chimes? To what purpose, I ask you, is the terrible snorting of bellows, more like a clap of thunder than the sweetness of a voice? Why that swelling and swooping of the voice? One person sings bass, another sings alto, yet another sings soprano. Still another ornaments and trills up and down on the melody. At one moment the voice strains, the next it wanes. First it speeds up, then it slows down with all manner of sounds. Sometimes – it is shameful to say – it is expelled like the neighing of horses, sometimes manly strength set aside, it is constricted to the shrillness of a woman’s voice. Sometimes it is turned and twisted in some sort of artful trill. Sometimes you see a man with his mouth open as if he were breathing his last breath, not singing but threatening silence, as it were, by ridiculous interruption of the melody into snatches.(1) Now he imitates the agonies of the dying or the swooning of persons in pain. In the meantime his whole body is violently agitated by histrionic gesticulations – contorted lips, rolling eyes, hunching shoulders – and drumming fingers keep time with every single note. And this ridiculous dissipation is called religious observance. And it is loudly claimed that where this sort of agitation is more frequent, God is more honourably served. Meanwhile ordinary folk stand there awestruck, stupefied, marvelling at the din of bellows, the humming of chimes and the harmony of pipes. But they regard the saucy gestures of the singers and the alluring variation and dropping of the voices with considerable jeering and snickering, until you would think they had come, not into an oratory, but to a theatre, not to pray but to gawk.

… sound should not be given precedence over meaning, but sound with meaning should generally be allowed to stimulate greater attachment. Therefore the sound should be so moderate, so marked by gravity that it does not captivate the whole spirit to amusement in itself, but leaves the greater part to the meaning. Blessed Augustine, of course, said, ‘The soul is moved to a sentiment of piety on hearing sacred chant. But if a longing to listen desires the sound more than the meaning, it should be censured.’ And elsewhere he says, ‘When the singing delights me more than the words I acknowledge that I have sinned through my fault, and I would prefer not to listen to the singer.’ [Aelred of Rievaulx: The Mirror of Charity, bk. II, ch. 23: ‘The vain pleasure of the ears’, tr. E. Connor, (Kalamazoo, 1990), pp 209-212.]

It was the job of the precentor and succentor (sub-cantor) to encourage singing in choir and also to ensure that everyone paid attention. Whoever did not sing devoutly was to be beaten.(5)

Mass and Communion

Velvet kneeler, embroidered burse, stole and maniple, thought to have belonged to the Cistercian monks of Abbey Dore © V&A

The Cistercians celebrated Mass, the sacramental meal instituted by Christ at the Last Supper, at least once a day. A second Mass was celebrated on Sundays and feast days, and additional masses were introduced throughout the course of the twelfth century, such as masses for the dead, the Virgin and benefactors. Monks who were ordained as priests generally celebrated a private mass each day at a side altar in the church.

© British Library

The celebration of Mass in a Cistercian abbey was kept as simple as possible. The celebrant was the monk appointed as priest for the week (the hebdomadary), who was assisted by the deacon, a sub-deacon and perhaps an additional helper. A Cistercian priest acted as deacon, but wore the stole around his neck as a priest and not across his shoulder, as a deacon. Like the Canonical Hours, Mass began with the Lord’s Prayer and the sign of the Cross. It ended with the Kiss of Peace, known as the Pax, but this was only exchanged by those who were about to receive Communion. The celebration of Mass was one of the few occasions when the Cistercians used incense in the church, which was otherwise regarded as an unnecessary expense.

Whereas most laymen and women received Communion up to three times a year, the Cistercian lay-brothers received Communion about seven times a year. Although Mass was celebrated daily, the Cistercian monks (other than the priest for the week [the hebdomadary]) only received the consecrated elements (the Host and the wine) on Sundays and feast days. This was, however, more frequent than other monks, such as the Black monks of Cluny, who received Communion monthly.

Communion followed the celebration of Mass. After exchanging the Kiss of Peace, the monks proceeded to the right of the altar where they were given the Host. They then walked behind the altar to the left side where they received the chalice containing the Blood of Christ, which was taken through a silver or gold-plated reed. From the mid-thirteenth century the chalice was reserved to those officiating at the altar and communicants only received the Host.(6)

At the close of the ceremony the altar cloths were removed. These were generally made of linen, but from 1256 the use of silk hangings was permitted.(7) Part of the consecrated bread and wine, known as the reserved sacrament, was kept in the church after the celebration of Communion. This was often suspended above the altar, the holiest part of the church (and also a safe place from vermin), or on a column in the presbytery. The reserved sacrament was primarily intended for distribution to sick members of the community.

Liturgical texts

“And because we receive in our cloister all their monks who come to us, and they likewise receive our monks in their cloisters, it therefore seems to us opportune, and this also is our will, that they have the usages and chant and all the books necessary for the day and night hours and for Mass according to the form of the Usages and books of the New Monastery, so that there may be no discord in our conduct, but that we may live by one charity, one Rule, and like usages.”

[Carta Caritatis clause III, in Waddell, Narrative and Legislative Texts, p. 444.]

The Cistercians initially followed the liturgical texts from the Benedictine abbey of Molesme, which Abbot Robert had brought with him on the group’s departure from here in 1098. A concern for greater accuracy, simplicity and common observance soon led to the revision and standardisation of these texts. This process began with Abbot Stephen Harding’s critical edition of the Bible, and was followed by a revision of the hymnal (the choir book of hymns used in the Canonical Hours) and the antiphoner (the choir book of chants sung at the Canonical Hours).

These revised texts were pronounced exemplars and were to be followed in every Cistercian abbey, to ensure uniformity of practice.

© British Library

© Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA . The antiphoner contained the choir book of chants sung at the Canonical Hours. Those sung at the Mass were in the gradual. (19)

© British Library

The Stephen Harding Bible (18)

The Stephen Harding Bible was the first work produced by the scriptorium of the New Monastery, later called Cîteaux. It was originally in two volumes, but now survives in four and is preserved in the Bibliothèque Municipale, Dijon (MSS 12-15). The first of the two volumes was completed in 1109, or at least the manuscript was written, if not illuminated by that date; the second volume is undated and very different in character. It includes the David Cycle (MS 14), a series of highly decorated miniatures illustrating the life of David. The Bible is today valued for its fine illuminations.

© Bibliothéque Municipal, Dijon

Music

Where, I ask, do all these organs in the church come from, all these chimes? To what purpose, I ask you, is the terrible snorting of bellows, more like a clap of thunder than the sweetness of a voice?

Why that swelling and swooping of the voice? (9) [Aelred of Rievaulx]

The Cistercians ruled against musical embellishment and strove to keep the chant as simple as possible, to ensure devotion and guard against frivolity. The General Chapter prescribed that monks should sing in manly voices without frills and trills, which were distracting and vain. In the mid-twelfth century Aelred of Rievaulx vehemently denounced musical embellishments. In a colourful invective he criticised the ‘swelling and swooping’ of voices, the ‘din of bellows and the humming of chimes’, and argued that far from enhancing religious observance, these histrionic displays and ‘saucy gestures’ made a mockery of worship. Aelred stressed that sound was of secondary importance and should merely augment the meaning.

The Cistercian monk in Idung of Prüfenings’ twelfth-century Dialogue criticised the Cluniacs for taking expensive liquorice cordials to help them reach the high notes when singing the Office; in the fourteenth century an English Cistercian, John Anglicus, debated whether or not choir monks should suck lozenges to improve their singing.

To ensure that music was kept as simple as possible the General Chapter prohibited organs in Cistercian churches until 1486. This ban was not heeded everywhere, for the earliest surviving organ music, which comes from Robertsbridge in Sussex, dates from c. 1350 and the abbey of Meaux in Yorkshire had two organs in the fourteenth century. (10)

The antiphoner contained the choir book of chants sung at the Canonical Hours. The monks shared these books which were generally large. Antiphoners were divided according to the days of the week (temporal) and feast days (sanctoral).(8) Chants that were sung at the Mass were in the gradual.

The antiphoner featured below dates from c. 1290 and was used in Cambrai. This manuscript is now in the Walters Gallery.

© Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA

References

(1) Les Ecclesiastica Officia Cisterciens du XII Siecle, ed. Choisselet, D. and P. Vernet (Reiningue, 1989), 75:44 (p. 222); Institutes, XLIX in Narrative and Legislative Texts from Early Cîteaux, ed. C. Waddell (Cîteaux, 1999), p. 477.

(2) Caesarius of Heisterbach, The Dialogue on Miracles, tr. H. Von E. Scott and C. C. Swinton Bland, 2 vols. (London, 1929), I, ch. XXXIV, p. 231.

(3) Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogue on Miracles, I, ch. XXXVIII, p. 234.

(4) Idungus of Prufung, ‘A Dialogue between Two Monks’ in Cistercians and Cluniacs: the Case for Cîteaux, tr. J. O’sullivan and L. Leahey (Michigan, 1977), I: 41 (p. 44).

(5) See C. Harper-Bill, ‘Cistercian visitation in the late Middle Ages: the case of Hailes Abbey’ , Bulletin of Historical Research LIII (1980), pp. 103-114 at p. 108.

(6) Statuta capitulorum generalium ordinis Cisterciensis ab anno 1116 ad annum 1786, ed. J. Canivez (8 vols; Louvain, 1933-41), II: 1261: 9.

(7) Canivez, Statutes II: 1256: 6.

(8) J. France, The Cistercians in Medieval Art (Stroud, 1998), p. 176.

(9) Aelred of Rievaulx: The Mirror of Charity, bk. II, ch. 23: ‘The vain pleasure of the ears’ , tr. E. Connor (Kalamazoo, 1990), pp. 209-212.

(10) J. France, The Cistercians in Medieval Art (Stroud, 1998), p. 173; Meaux Chronicle III, p. lxxxii..