by Mark Hall, Paula Goodale, Paul Clough and Mark Stevenson

1. Introduction

Over the past years large digital cultural heritage collections have become available, for example Europeana1 holds over 22 million items, while the UK National Archives digital index2 contains approximately 11 million items. However, this vast amount of material can also be overwhelming and difficult to access since users are provided with little or no guidance on the information in these collections. Users are typically offered simple keyword-based search interfaces as the sole access mechanism to the collection. This access paradigm successfully supports expert users,3 as these users are familiar with the collections, have specific information needs, and know which keywords to use to satisfy these information needs.

However, non-expert users are often unfamiliar with the content of collections, making keyword-based search unsuitable since they are unable to formulate appropriate queries.4 The problem is summarised by Borgman:5

“So what use are the digital libraries, if all they do is put digitally unusable information on the web?”

An additional problem is that the Information Retrieval (IR) systems currently applied in digital cultural heritage only support a small fraction of the information seeking process6 forcing users to augment the IR systems with other tools. To support the whole information seeking process for both experts and novices, IR systems are required that provide an initial overview of the collection,7 functions for exploring collections,8 such as thesauri9 and faceted browsing,10 somewhere to collect potentially relevant items, and finally the ability to organise the items into a sense-making structure.

The PATHS (Personalised Access To cultural Heritage Spaces) project addresses these issues by providing a novel framework for exploring large digital cultural heritage collections. The core approach is based around the metaphor of a path through the collection, which is a structured set of items that takes the new user on a journey through parts of the collection. These paths can be created explicitly or implicitly as the user explores the collection. Users can also follow pre-defined paths created by domain experts, such as scholars or teachers. Additionally through a number of content processing methods, the system entices the user to leave the beaten path and explore the collection on their own. The goal is to transform the new user from a passive consumer into an active explorer and contributor.

Paths provide an easily accessible entry point to the collection that can be either followed in their entirety or left at any point. They can be based around any theme, for example artist and media (“sculptures by Henry Moore”), historic periods (“the Industrial Revolution”), places (“London”), famous people (“Coco Chanel”) or any other topic (e.g. “Europe” or “horses in art”).

This paper begins by describing alternatives to keyword-based search (see Section 2) and an analysis of people’s views on the path metaphor (see Section 3). These are used to inform the design of a system (see Section 4), which is then implemented (see Section 5) and evaluated (see Section 6). The paper concludes by discussing future directions for exploration interfaces for digital cultural heritage collections.

2. Background

The limitations of the search box in providing support for new users to explore the collection have led to the development of a number of alternative exploration techniques, including path-like structures, faceted search User Interfaces (UIs), and other visualisation techniques. These search interfaces have been shown to be more suitable for exploratory search than keyword-based approaches.11

We considered a range of possible approaches when designing the PATHS system which we describe here. The path metaphor is relatively common in the cultural heritage domain,12 particularly in the form of guided tours and has also be used in digital form (Table 1). The originator of this approach was the Walden’s Path system13 which was aimed at the educational context and enabled educators to chain together web-pages into learning objects, which were then available via the web for access by the learner. One of the issues Walden’s Path had was getting people to create and share paths. A possible solution is to automate the path creation process. Joachims et. al14 describe a system for automatically guiding users through a web-site. However, in a controlled test only about half the users found the system to be helpful, demonstrating the difficulty with automated approaches. It is due to the difficulty of attracting general contributors, that the decision was to focus the initial work on heritage and education professionals who have an intrinsic motivation for creating and sharing paths.

Table 1: Sample of web-sites and on-line tools that use the path metaphor.

| Walden’s Paths | Learning resource & path-creation tools | Teachers & Students | http://walden.csdl.tamu.edu/walden/server |

| First World War Poetry Digital Archive | Learning resources & path-creation tools | Teachers & Students | http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/education/pathways |

| The Louvre | Visitor resources | General visitors | http://www.louvre.fr/llv/activite/liste_parcours.jsp?bmLocale=en |

| Connected Histories | Research resources | Academic researchers | http://www.connectedhistories.org/research_connections.aspx |

| Storify | Content curation | Bloggers & social media users | http://storify.com |

| Pearltrees | Mind map trees | Bloggers & general users | http://www.pearltrees.com |

Following a path represents the first step, but the aim is to then enable free exploration of the collection. Controlled vocabularies are often seen as a promising discovery methodology.15 However, in the case of aggregated collections such as Europeana, the collection we are working with, items from different providers are frequently aligned to different vocabularies, requiring an integration of the two vocabularies in order to present a unified structure.

Manual creation of a unified hierarchy would produce the best results,16 but with collections of millions of items that is not feasible. Issac et. al17 describe the use of automated methods for aligning vocabularies, however that is not always successfully possible and even if it is, does not provide a solution for those items that are not attached to any vocabulary. An alternative is to automatically create a new hierarchy that covers the whole collection. A number of approaches exist including using subsumption,18 sub-string matching,19 mapping items into an existing hierarchy,20 or using statistical models.21

Where no vocabularies are available or cannot be generated with sufficient quality, faceted search interfaces22 offer an alternative UI that provides an overview and enables a limited amount of exploration. The problem with faceted search and large collections is that usually there are a large number of facet values to display that exceed the amount of space available in the UI, severely limiting their utility in gaining an overview. There have been attempts at integrating hierarchy information into the facets, enabling them to scale, however this raises the question of where to get the hierarchy from.

Time-lines such as those proposed by Luo et. al23 do not suffer from these issues, but are only of limited value if the user’s interest cannot be focused through time. A user interested in examples of pottery across the ages or restricted to a certain geographic area is not supported by a time-line-based interface.

Alternative exploration UIs have been proposed, including 2-dimensional semantic maps,24 multi-dimensional scaling,25 self-organising maps,26 and dynamic taxonomies.27 While these have all been shown to improve the exploration experience, they have not seen widespread use, either due to the complexity of their implementation in a real-world scenario or because they struggle to scale to large collection sizes.

In the PATHS project we aim to integrate a number of these exploration interfaces, including vocabularies, 2-dimensional maps, and faceted search interfaces, into the path metaphor to create an integrated system for exploring large digital cultural heritage collections.

3. Paths Through Cultural Heritage

To develop the PATHS system we used a user-centred methodology, which involves the prospective users at all stages of the development, ensuring that the resulting system is fit for purpose. The core development process followed a standard three-phrase approach, consisting of the initial user requirements acquisition, the design and implementation, and then the evaluation phase. While the design and implementation are specific to the PATHS project, the insights gained from the requirements analysis and evaluation apply to any system attempting to provide exploration facilities for digital cultural heritage collections.

3.1. Structured Interviews

The first phase in the user requirements acquisition was to investigate how the path concept is interpreted and used in the cultural heritage and education domains, which we identified as the primary application domains. Fourteen in-depth interviews were undertaken, with professionals in a variety of roles, from cultural and academic institutions.

The initial questions were focused on discovering what the concept of a path meant to the interviewees. In the answers we found two main strands. First is the use of a path as a method for introduction to a collection or topic, with participants stating that the paths could be created explicitly by a user, implicitly based on the user’s path as they berry-pick28 their way through the collection, or simply based on popularity. The second concept is the path as a learning object and information literacy journey. The idea is that at the end of the journey along the path the user has not only developed a deeper understanding of the path’s topic, but also of how the wider collection is structured and what kinds of items are in the collection. Based on this we designed the PATHS system to support both explicit and implicit path creation. While the primary interaction method will be manually curated paths, the system will log all of a user’s interactions and from this derive the implicit paths.

From the basic use of paths, the interview then focused on understanding the potential structures that a path can take. There was general agreement that the basic structure is a set of items that are linked together in some way, where possible providing branches that give the user a choice of where to go. There was a general idea that while paths have a start and an end, the user should be able to join the path wherever they want and at the end there should be a smooth transition into the wider collection, enabling the user to freely explore. The most interesting aspect of the responses was the amount of focus the interviewees placed on the narrative as a core aspect of the path. For the interviewees the narrative was what set the path apart from similar structures such as simple lists of items or guided tours. Particularly noteworthy was the distinction between a guided tour and a path. Paths were seen as less formal, shorter, and more focused on storytelling than guided tours. As a result the PATHS system was designed to make it as simple as possible for the user to add narrative to their paths.

3.2. Path Creation Studies

To further understand the potential structures a path can take we ran two further studies, one within the project partners, one with a group of master’s students. In the first we asked project partners to create paths using whatever tools they wanted to use and on whatever topic they were interested in. In the second study 19 students were split into groups and each group given one of five topics and asked to create a path using pen and paper.

Figure 1: An example path created as part of our path creation study.

The path uses a linear structure of items arranged vertically.

Figure 2: An example path created as part of our path creation study.

The path uses a tree-like structure with two shared nodes, before it branches to describe different aspects of the topic.

Figure 3: An example path created as part of our path creation study.

The path uses a graph-like structure that provides the user with maximum freedom to explore, but is also harder to navigate.

An analysis of the paths created in this exercised revealed three structural patterns that covered the majority of paths:

- Linear paths (Figure 1) have a single start and end-point and a linear narrative joining these two together.

- Tree-like paths (Figure 2) have a single starting point, but then branch into a number of parallel paths that explore different facets of the path’s topics. Two sub-types of this structure were observed. The first covered paths that had a number of nodes before branching (as shown in the example in Figure 2) and those that were closer to a centre-and-spoke pattern with the branches all originating at the first node.

- Graph-like paths (Figure 3) have no clear starting point, instead featuring a network of connections between the path nodes. These kinds of paths support a very free exploration of the path structure, however they also present a problem with regards to supporting the user in creating and exploring such paths.

For the designs presented in the next section, only linear paths were considered, primarily due to time constraints within the project. Tree-like paths are planned for the next version of the system, while graph-like paths are left for future work.

4. Design and Implementation

Based on the expert interviews and the path creation studies a theoretical model of path interaction and creation was created (Figure 4). The model consists of the following five activities with a number of potential transitions between them:

Figure 4: The theoretical model of path interactions derived from the expert interviews and path creation study.

The PATHS system supports the four main activities (Consume, Collect, Create, Communicate).

Concept focuses on the development of the concept the user is interested in and is mostly conducted outside the PATHS system. However, interaction with the Collect and Consume activities can lead to the concept being changed or refined as the user explores the collection.

Collect involves gathering the nodes that will form the path. This activity can be conducted using whatever search and exploration methods the system provides regardless of whether these are a traditional linear IR model, berry-picking, or an overview-based system.

Create takes the collected nodes and forms them into a path. Nodes can be collected explicitly through the Collect activity or implicitly through the process of Consuming existing paths (i.e. through on-line log mining). The Create activity also allows the creator to annotate the nodes to provide a narrative for the path. The model supports switching between the Create and Collect activities, as arranging the nodes can highlight gaps in the path that need to be filled.

Communicate is centred on sharing nodes, collections of nodes, and paths between users either within the PATHS system or with existing social networks such as Twitter or Facebook to support the social dimension29 of interacting with cultural heritage information.

Consume will frequently be the first activity most users participate in, taking them into areas of the collections that they have not previously explored. The PATHS system will use automatic adaptation based on cognitive styles and manual preferences, with the goal of improving learning outcomes.30 While Consume is meant to be the primary entry-point for the casual user, the tight linkage with the Collect and Create activities indicates that the goal is to transition the user from consumption to path creation.

Figure 5: A sample of potential interactions between different user groups and the path-interaction model.

The model’s strength lies in the combination of flexible transitions between activities, which are at the same time limited enough that the UI can take advantage of them. The flexibility is necessary as different users have different preferred interaction patterns (Figure 5). For example a curator is likely to develop the concept for their path, and then collect the items that they need to explain that concept. From these they create the path, which is then communicated to its target audience. On the other hand educators tend to want to leave out the creation step, instead communicating the items collected for the concept to their target audience, with the goal that these then in the learning process create a path, arranging the items into their view of the concept. Finally, the casual user, who is most likely to find out about the system via some form of communication, starts with consuming paths and either implicitly or explicitly collects items along the way. In the spirit of the path as an information literacy journey, the goal of the model is that it supports the user in transitioning from a passive consumer to an active creator, when they create and communicate their own path through the collection.

4.1. Design

From the theoretical model we derived a system design consisting of three sections: path following, free exploration, and path creation.

4.2. Path Following

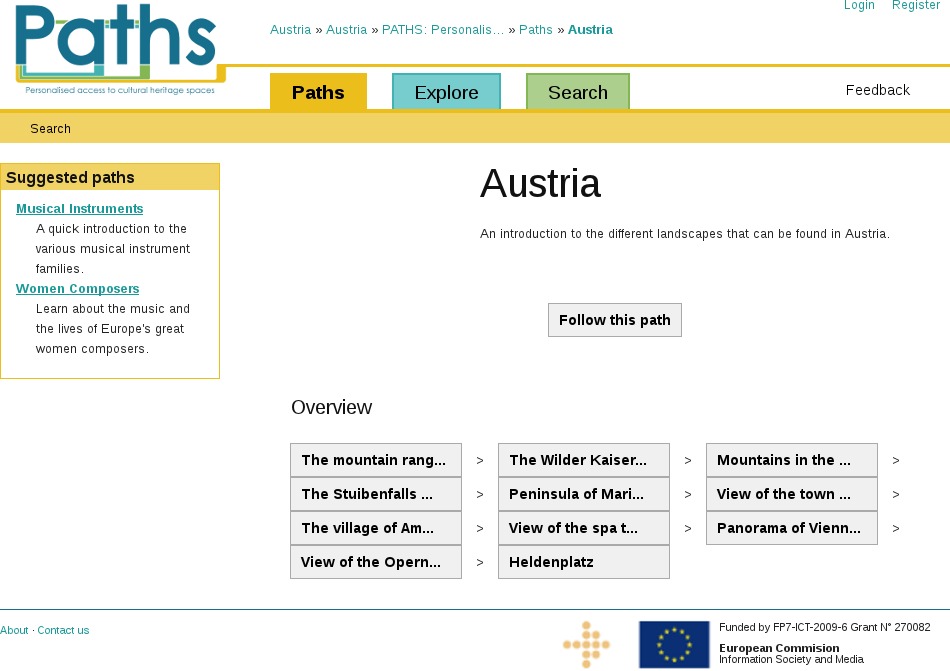

Figure 6: The path overview design.

It includes the path’s title and narrative overview, together with a simple display of the nodes in the path, enabling the user to start anywhere in the path.

Figure 6 shows the design for the initial path overview page. It displays the path’s title and narrative overview. Based on the interviews we also included a more visual overview over the path, which additionally enables the user to select where they wish to start the path. The design also includes a list of related paths, to hopefully increase the chances of the user serendipitously discovering paths and items of interest.

Figure 7: The path following design.

It includes the narrative the path creator added and also the similar items and background information links designed to encourage exploration.

Figure 7 shows the design for the path following page that takes the user through the individual nodes of the path. It shows the original item’s thumbnail and the title and narrative that the path creator added. On the left, the “similar items” are designed to entice the user into exploring the collection on their own, while the “Background links” provide additional context information that helps the user in interpreting the item. The buttons above the page’s title enable the user to move backwards and forwards through the path and were added based on the initial evaluation results (see section 6).

4.3. Free Exploration

Figures 8, 9, 10, and 11 show the various designs for the exploration section of the system. The simplest is in figure 8, demonstrating the use of a tag-cloud to enable free exploration. As the user selects tags from the tag-cloud, the list of items shown below the tags is narrowed down to those items that belong to all the tags the user has selected.

Figure 8: The tag-cloud exploration design.

It allows the user to drill down into the subject tags and see the items that have been assigned to the selected tags.

Figure 9: The hierarchical vocabulary exploration design.

It provides a more topic-based exploration facility.

Figure 9 demonstrates the integration of a hierarchical vocabulary into the exploration process. The top-left corner shows the current branch the user is exploring, while in the centre the items belonging to the currently selected vocabulary topic are shown. In figure 10 the user can explore a different set of topics using a visual approach where each topic is illustrated using four thumbnails drawn from the items that belong to the topic.

Figure 10: The visual exploration design.

It provides a more visual overview over the items available in the collection.

Finally, Figure 11 shows the faceted search UI used to provide the PATHS system’s search functionality. The provision of a full search system ensures that those users who are or have become sufficiently familiar with the collection can easily locate the specific items and paths they are interested in.

Figure 11: The faceted search design.

It follows best-practices in faceted search design.

4.4. Path Creation

Figure 12 demonstrates the workspace into which users can collect items that they wish to save for later or for use in one of their own paths. From strong narrative focus we found in the expert interviews, we derived the need to give the user the immediate option of annotating any items they collect, to make an early start on creating the narrative. From the workspace the user can then create their own path (Figure 13). When the user creates a new path, all items in the workspace are automatically transferred into the new path, including any annotations made in the workspace. In the path editing interface the user then uses drag-and-drop to re-order the items into the order they want them to be in their path. By clicking on the path item’s edit button the user can then expand on the narrative. The editor provides a what-you-see-is-what-you-get editing interface, enabling the user to easily develop the rich narratives that the initial interviews stated are the core of a good path.

Figure 12: The workspace used by the user to collect items of interest.

The user can immediately add narrative to the collected items, if they wish to do so.

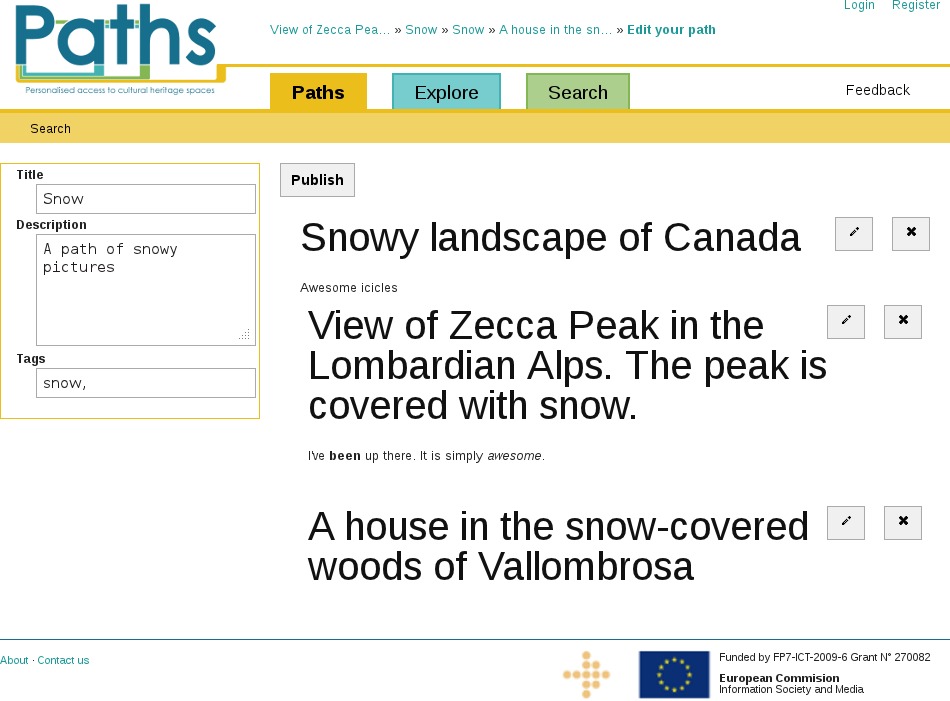

Figure 13: The path editing interface.

It uses drag-and-drop to arrange the items in the path and allows the user to use rich text editing facilities to add their narrative.

4.5. Implementation

The designs were implemented using the three-tier architecture in Figure 14. The backend server holds all the cultural heritage data, the augmented data generated in the loading step, and the paths created within the system. The loading component is responsible for taking the source data from Europeana, transforming it into the PATHS data model, running the data augmentation processes, and then storing the results in the backend. The frontend server then accesses the data through a series of web-services provided by the backend. The use of a web-service interface between the frontend and backend enabled the development to easily be split across project partners and also makes it possible to have different user interfaces, without having to duplicate the backend functionality. Currently a mobile client and social media integration are planned as additional user-interfaces. The final user interface is created using HTML and CSS and displayed in the user’s browser. JavaScript is used to provide progressive enhancements and a smoother interaction experience when available. Following web-development best-practices the system’s functionality is available without JavaScript, with the exception of the path creation which requires JavaScript.

Figure 14: The three-part architecture used in the PATHS system.

It shows how additional user-interfaces can plug into the existing backend functionality to simplify their development.

Video of the final PATHS system in action: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EEtebfhcKjQ

4.6. Data

The data used for the PATHS system was a collection of approximately 1.8 million items drawn from the English (>0.5 million items) and Spanish (>1.2 million items) collections within Europeana. This content was chosen since our project consortium included organisations with expertise in these two languages.

Before being included in the system the data was pre-processed to add background links to Wikipedia and links between similar items. The background links provide additional information about each item which supplements the (often very limited) information available in Europeana. The links between similar items allows users to easily identity items related to a specific topic in the collection and have been shown to be useful for supporting exploration of cultural heritage content.31

The Wikipedia background links were created by running the WikiMiner software over the items’ titles and descriptions, linking each item to Wikipedia articles that are mentioned in the text.32 The WikiMiner software produces a confidence value for each link, describing how certain it is that the link is to the correct item. Only links with a confidence of over 0.5 were retained for the final system.

To create the similar-item links, two Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) models consisting of 700 topics each were calculated, one for the English and one for the Spanish data.33 For each item the LDA model was then used to determine to which topics the item belongs and to what degree it belonged to each of those topics. This data was then used to determine the similar-items links between items by selecting the 25 items whose topic assignments were most similar to those of the item the links were being added to.

The collection does not have a consistent vocabulary and efforts to automatically generate vocabularies were not sufficiently successful to enable their use. Thus only the tag-cloud and faceted search exploration interfaces were enabled and evaluated.

5. Evaluation

To determine whether the system achieved its goals it was evaluated using two different approaches. First a cognitive walkthrough34 was performed to ensure that the basic functionality was implemented and clearly understandable to the user. Second, a full task-based user study was performed to validate the system in a realistic scenario.

5.1. Cognitive Walkthrough

A cognitive walkthrough is an exercise conducted by a usability expert, who critically analyses the user interface as they try to complete a series of tasks that are common in the interface under test. The following three tasks derived from the path interaction model were tested:

- Consume a path by finding and following it.

- Collect items for a path.

- Create a new path from the collected items.

From the cognitive walkthrough a number of issues with the interface were identified, primarily around the path following interface. These mainly revolved around the ability to navigate through the path. The initial designs had included only a button for moving to the next page of the path and to get back the user was expected to use the browser’s back button. To correct this, an explicit backward navigation button was added. The usability expert also judged the path overview to be confusing, so it was re-structured into a vertical list. The cognitive walkthrough also identified issues in the interaction between the exploration using the tag clouds and the search interfaces, but these could not be corrected before the main user study was conducted.

5.2. User Evaluation

The main evaluation was conducted with 22 participants, recruited in three different categories: general museum visitors; people using cultural heritage material for study purposes; and people using cultural heritage material for work purposes in research, educational and curatorial roles. These participants therefore represent a variety of novice and expert users, with varying degrees of domain, subject and technical (IT) skills. Each session lasted between one and a half and two hours and followed the protocol specified in Table 2.

Table 2: The nine-step research protocol used in the final user-evaluation.

| User profile | A set of responses acquired to describe the sample of evaluation participants |

| CSA | The Cognitive Style Test35 was administered to determine whether that had any impact on the use of the system |

| System familiarisation | A short period of time where the participants were introduced to the PATHS system and given a brief tour |

| Simulated work tasks (simple fact-find, extended fact-find, open ended browsing, exploration) | A set of four short tasks |

| Post-task feedback | A set of quantitative and qualitative responses to the simulated work tasks |

| Long unstructed simulated work task | The main evaluation task in which the participants went through the whole workflow of collecting items and then forming them into a path |

| Post task feedback | A set of quantitative and qualitative responses to the long unstructured work task |

| Session feedback | Qualitative feedback on the whole session |

| Think after interview | Participants were shown a screen recording of the path creation task and asked to narrate their experience |

In general participants were able to successfully complete both the short tasks and the long path-creation task. The analysis is thus focused less on whether they were successful, but on what issues they encountered in the process of completing the tasks. The results of the qualitative responses and the “Think after interview” highlighted some interesting issues with the system, from which we can also infer some general conclusions about what systems providing access to digital cultural heritage need to provide.

On the positive side, the core functionality of the system, namely following paths and also creating paths, was judged to be easy to use and useful by 15 of the participants. At the same time, issues highlighted in the cognitive walkthrough were also raised by the participants. The facilities for navigating around the path were judged to be limiting, even after the modifications applied based on the cognitive walkthrough. Participants wanted some kind of visual overview over the whole path that would allow them to jump around the path however they wished. They also expressed the wish to create more complex path structures, an outcome that informs any future systems that provide paths or path-like structures.

The most striking aspect of the study is that the interface that participants struggled with most was the individual item view. Only 8 of the 22 participants judged the item viewing page to be useful and easy to use. An in-depth analysis of the qualitative responses reveals that the underlying issue is the quality of the data. Due to the aggregate nature of the collection, many items have very little meta-data, and where there is meta-data it is frequently limited to a word or two. This created item viewing pages that had very little content and were thus of very little use to the participants. The problem was exacerbated by the information retrieval algorithms used by the system, as these ranked documents that had little meta-data higher than those with more meta-data. This is because items with more meta-data are judged to be less similar to the user’s query than those that have little meta-data, but what meta-data there is matches the user’s query exactly. Based on this we conclude that standard information retrieval systems have to be tuned to the peculiarities of cultural heritage data, where items with more meta-data are generally more useful than those with less, even if it means that, from a purely numeric point of view, the query is not as precise a match to the item. Where the meta-data cannot be improved through manual curation, automatically augmenting the meta-data is a viable way forward, as participants were generally positive about the additional context the background links and similar items provided.

Exploration of the collection was the other area that participants struggled with, and again issues with the data were the primary hurdle. Due to the lack of vocabularies, the exploration was limited to the tag-cloud. This limitation was made worse by the fact that the Spanish data outweighed the English data and that the Spanish data contained cataloging information in the subject meta-data fields used to create the tag-cloud. As a result only very few English tags were visible at the top level and although tag-clouds calculated from only the English data were also provided, participants struggled with exploring the collection using the tag cloud.

The search functionality was generally well received, with 13 participants rating it as easy or very easy to use. The main criticism and suggestions derived from the fact that the search system did not provide functions that users have come to expect from search engines, such as query suggestion, spell-checking, and sorting options. These results clearly apply to the wider field of digital cultural heritage systems.

Issues with the data again impacted the usefulness of the search results. Frequently the search returned multiple items where all the meta-data shown in the search results (title and a snippet taken from the item’s description) was the same. Participants suggested collapsing the items together, which would enable more variability in the search results, an option that clearly can be generalised to digital cultural heritage systems in general. An open question with this approach is how much variation in the hidden meta-data is allowed within the items that have been collapsed together.

A general comment made throughout the sessions was regarding the quality of the thumbnail images. Participants wanted to be able to view higher-resolution versions of the images to determine whether the item was of interest. This clearly corresponds with36 findings that interaction in digital cultural heritage is a very visual activity. However, Europeana only provides thumbnails, which frustrated users.

The second frequent general comment was that participants wished for a smoother integration between the various components of the system. They wanted to execute a query, then switch to a tag-cloud of the search results and use the tag-cloud to explore the search results. Similarly when in the tag-cloud, participants wanted to search within the current tag-cloud. Similar integration suggestions were made with respect to finding paths and switching between path following and search. The conclusion from this is that while the path interaction model derived from the initial interviews is useful in supporting the user, the transitions between the activities have to be hidden so that the user is not aware of when they switch between activities.

Finally participants mentioned that they would like to see more structured support for exploring the collection, at least in the form of a set of high-level topics, but if possible via the provision of a full hierarchical vocabulary that can be explored. This clearly indicates that where no such vocabulary exists for a collection, work on automatically creating such vocabularies is an important research focus.

6. Conclusions

In this paper we presented the PATHS system for exploring large digital cultural heritage collections. The system is based around the concept of a path, that is a sequence of items drawn from the collection that are linked together by a narrative written by the path’s creator. The aim of the path is to provide an introduction to both the path’s topic and the wider collection for the new user who is unfamiliar with one or the other. To ensure that the system fulfilled this goal a user-centred design methodology was adopted. Based on an extensive set of interviews conducted to determine how people interpret, use, and create paths, we developed a model of path interaction and creation, that enables the PATHS system to support the user in their complete information seeking journey, from initially consuming paths to exploring the collection independently to finally creating their own paths.

The PATHS system was evaluated in a user-study that highlighted a number of usability issues, but also some more general guidelines that apply to any system that enables the exploration of digital cultural heritage collections. The central guideline is that the quality of the meta-data and the availability of high-resolution images for the items is paramount for a positive user experience. Where the meta-data is limited, the user-study has shown that automated methods of augmenting the data are well received. The second general guideline is that any system that provides a search interface should provide search support functions that users have come to expect, such as query suggestion and spell-checking. The final conclusion is that users want and need support in exploration that goes beyond simple methods such as tag clouds or faceted search. The support mechanism should include at least a very high level set of topics, but ideally would include a full hierarchical vocabulary for users to explore.

In future work we intend to address the issues raised in the evaluation, particularly around the need for some kind of hierarchical vocabulary to support exploration. We also intend to investigate the use of recommendations to support exploration across topics. Finally we intend to apply the PATHS system to other data collections, to ensure that it is flexible and can also be applied to collections outside the cultural heritage domain.

7. Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results was carried out as part of the PATHS project (http://paths-project.eu) funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 270082.

- The European Digital Library, http://www.europeana.eu

- The UK National Archives, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

- Sutcliffe, Alistair and Mark Ennis. Towards a cognitive theory of information retrieval. Interacting with Computers, 10:321–351, 1998.

- Wilson, M.L., Kules B, Schraefel MC, and Shneiderman B. From keyword search to exploration: Designing future search interfaces for the web. Foundations and Trends in Web Science, 2(1):1–97, 2010; Guntram Geser. Resource discovery – position paper: Putting the users first. Resource Discovery Technologies for the Heritage Sector, 6:7–12, 2004; Michael Steemson. Digicult experts seek out discovery technologies for cultural heritage. Resource Discovery Technologies for the Heritage Sector, 6:14–20, 2004; Mark M Hall, Oier Lopez de Lacalle, Aitor Soroa, Paul D Clough, and Eneko Agirre. Enabling the discovery of digital cultural heritage objects through wikipedia. In Proceedings of the LaTeCH workshop held at EACL 2012, 2012.

- Christine L. Borgman. The digital future is now: A call to action for the humanities. Digital humanities quarterly, 3(4), 2009.

- C.C. Kulthau. Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 42(5):361–271, 1991;

- Kasper Hornbæk and Morten Hertzum. The notion of overview in information visualization. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69(7-8):509 – 525, 2011.

- Gary Marchionini. Exploratory search: From finding to understanding. Communications of the ACM, 49(4):41–46, 2006; Peter Pirolli. Powers of 10: Modeling complex information-seeking systems at multiple scales. Computer, 42(3):33–40, 2009.

- A.A. Shiri, C. Revie, and G. Chowdhury. Thesaurus-enhanced search interfaces. Journal of information science, 28(2):111–122, 2002.

- M.A. Hearst. Clustering versus faceted categories for information exploration. Communications of the ACM, 49(4):59–61, 2006.

- See Gary Marchionini 2006

- J. Heitzman, C. Mellish, and J. Oberlander. Dynamic Generation of Museum Web Pages: The Intelligent Labelling Explorer. Archives and Museum Informatics, 11(2):117–125, 1997; K. Grieser, T. Baldwin, F. Bohnert, and L. Sonenberg. Using Ontological and Document Similarity to Estimate Museum Exhibit Relatedness. Journal of Computing and Cultural Heritage, 3(3):1–20, 2011; M. O’Donnell, C. Mellish, J. Oberlander, and A. Knott. ILEX: An architecture for a dynamic hypertext generation system. Natural Language Engineering, 7:225–250, 2001.

- Frank Shipman, Catherine Marshall, Richard Furuta, Donald Brenner, Hao-wei Hsieh, and Vijay Kumar. Creating educational guided paths over the world-wide web. In Proceedings of Ed-Telecom, vol 96, 326–331, 1996; Frank Shipman III, Richard Furuta, Donald Brenner, C.C. Chung, and Hao-wei Hsieh. Using paths in the classroom: experiences and adaptations. In Proceedings of the ninth ACM conference on Hypertext and hypermedia, 267–270. ACM, 1998.

- T. Joachims, D. Freitag, T. Mitchell, et al. Webwatcher: A tour guide for the world wide web. In International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol 15, 770–777. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd, 1997.

- Murtha Baca. Practical issues in applying metadata schemas and controlled vocabularies to cultural heritage information. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 36(3–4):47–55, 2003.

- Ramana Rao, Jan O. Pedersen, Marti A. Hearst, Jock D. Mackinlay, Stuart K. Card, Larry Masinter, Per-Kristian Halvorsen, and George C. Robertson. Rich interaction in the digital library. Communications of the ACM, 38(4):29–39, April 1995; L. Rosenfeld and P. Morville. Information architecture for the World Wide Web: Designing large-scale Web sites. O’Reilly Media, Incorporated, 2002.

- Antoine Isaac, Stefan Schlobach, Henk Matthezing, and Claus Zinn. Integrated access to cultural heritage resources through representation and alignment of controlled vocabularies. Library Review, 67(3):187–199, 2007.

- M. Sanderson and B. Croft. Deriving concept hierarchies from text. In Proceedings of the 22nd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, pages 206–213. ACM, 1999.

- P.G. Anick and S. Tipirneni. The paraphrase search assistant: terminological feedback for iterative information seeking. In Proceedings of the 22nd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, pages 153–159. ACM, 1999; C.G. Nevill-Manning, I.H. Witten, and G.W. Paynter. Lexically-generated subject hierarchies for browsing large collections. International Journal on Digital Libraries, 2(2):111–123, 1999.

- E. Stoica, M.A. Hearst, and M. Richardson. Automating creation of hierarchical faceted metadata structures. In Human Language Technologies: The Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL-HLT 2007), pages 244–251, 2007; R. Navigli, P. Velardi, and A. Gangemi. Ontology learning and its application to automated terminology translation. Intelligent Systems, IEEE, 18(1):22–31, 2003; D.N. Milne, I.H. Witten, and D.M. Nichols. A knowledge-based search engine powered by wikipedia. 2007.

- D. Lawrie, W.B. Croft, and A. Rosenberg. Finding topic words for hierarchical summarization. In Proceedings of the 24th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, pages 349–357. ACM, 2001; David M. Blei, Thomas Griffiths, Michael Jordan, and Joshua Tenenbaum. Hierarchical topic models and the nested chinese restaurant process. In NIPS, 2003.

- Jacco van Ossenbruggen, Alia Amin, Lynda Hardman, Michiel Hildebrand, Mark van Assem, Borys Omelayenko, Guus Schreiber, Anna Tordai, Victor de Boer, Bob Wielinga, Jan Wielemaker, Marco de Niet, Jos Taekema, Marie-France van Orsouw, and Annemiek Teesing. Searching and annotating virtual heritage collections with semantic-web technologies. In Museums and the Web, 2007; Patrick L Schmitz and Michael T Black. The delphi toolkit: Enabling semantic search for museum collections. In Museums and the Web 2008: the international conference for culture and heritage on-line, 2008.

- Dongning Luo, Jing Yang, Milos Krstajic, William Ribarsky, and Daniel A. Keim. Eventriver: Visually exploring text collections with temporal references. Visualization and Computer Graphics, IEEE Transactions on, 18(1):93 –105, 1 2012.

- Keith Andrews, Christian Gutl, Josef Moser, Vedran Sabol, and Wilfried Lackner. Search result visualisation with xfind. In uidis, page 0050. Published by the IEEE Computer Society, 2001.

- Blaz Fortuna, Marko Grobelnik, and Dunja Mladenic. Visualization of text document corpus. Informatica, 29:497–502, 2005; Glen Newton, Alison Callahan, and Michel Dumontier. Semantic journal mappiong for search visualization in a large scale article digital library. In Second Workshop on Very Large Digital Libraries at ECDL 2009, 2009.

- Xia Lin. Visualization for the document space. In Proceedings of the 3rd conference on Visualization ’92, VIS ’92, pages 274–281. IEEE Computer Society Press, 1992.

- Panagiotis Papadakos, Stella Kopidaki, Nikos Armenatzoglou, and Yannis Tzitzikas. Exploratory web searching with dynamic taxonomies and results clustering. In Maristella Agosti, José Borbinha, Sarantos Kapidakis, Christos Papatheodorou, and Giannis Tsakonas, editors, Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries, volume 5714 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 106–118. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg, 2009; Chaomei Chen, Timothy Cribbin, Jasna Kuljis, and Robert Macredie. Footprints of information foragers: behaviour semantics of visual exploration. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 57(2):139 – 163, 2002.

- Marcia J. Bates. The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Information Review, 13(3):407–424, 1989.

- Yasuyuki Sumi and Kenji Mase. Agentsalon: Supporting new encounters and knowledge exchanges by chats of personal agents. In CHI’01 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems, pages 191–192. ACM, 2001; Margaret H Szymanski, Paul M Aoki, Rebecca E Grinter, Amy Hurst, James D Thornton, and Allison Woodruff. Sotto voce: Facilitating social learning in a historic house. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 17:5–34, 2008; Shelley Bernstein. Where do we go from here? continuing with web 2.0 at the brooklyn museum. In Museums and the Web 2008: the international conference for culture and heritage on-line, 2008.

- Amy Isard. Choosing the best comparison under the circumstances. In Workshop on Personalised Access to Cultural Heritage (PATCH07), pages 39–50, 2007.

- K. Grieser, T. Baldwin, F. Bohnert, and L. Sonenberg. Using Ontological and Document Similarity to Estimate Museum Exhibit Relatedness. Journal of Computing and Cultural Heritage, 3(3):1–20, 2011.

- Samuel Fernando and Mark Stevenson. Adapting wikification to cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Language Technology for Cultural Heritage, Social Sciences, and Humanities, pages 101–106, Avignon, France, April 2012. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- N. Aletras, M. Stevenson, and P. Clough. Computing similarity between items in a digital library of cultural heritage. Journal of Computing and Cultural Heritage, 5(4):no. 16, 2012.

- Sharp H, Rogers Y, and Preece J. Interaction Design: beyond human-computer interaction (2nd ed.). Chishester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2007.

- Riding R J. Cognitive style analysis: Administration. Birmingham: Leanring and Training Technology, 1991.

- M. Skov and P. Ingwersen. Exploring information seeking behaviour in a digital museum context. In Proceedings of the second international symposium on Information interaction in context, pages 110–115. ACM, 2008.