by Beatrice Gelosia, Alessandra Giovenco, Stephen J. Milner and Valerie Scott

1. Introduction

Figure 1: The BSR building

Founded in 1901, the British School at Rome (BSR) is the largest of the UK’s British International Research Institutes (BIRI), and has a long history as a catalyst for academic research and creative practice across the Mediterranean and North Africa (Wiseman 1990; Wallace-Hadrill 2001) (Figure 1). Our historic strength in the fields of the humanities and social sciences, visual art and architecture means we have always worked as an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary institution, engaging with a wide variety of media. Since its inception, the BSR has accumulated unique special collections, including over 3,600 rare books and some 100,000 photographic items, prints, drawings, engravings and other works of art. Our own institutional archive contains records regarding the building of the initial Lutyens façade for the 1911 International Exhibition in Rome, the setting-up of the various scholarships and awards, records of all the award-holders from 1912 onwards, and the history of the BSR’s relations with institutions across the UK and Commonwealth, including the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, the Royal Academy of Arts and the Royal Institute of British Architects.

These unique primary resources continue to be a key focal point of the BSR’s own research work and digital humanities activities. Our activities have increasingly focused on digitisation as a means of establishing interdisciplinary dialogue, as well as critiquing, sharing and enriching interaction with external audiences. In recent years, the BSR has increased its investment in a broad range of research activities and artistic practices with a digital dimension. As a central part of the UK government’s Industrial Strategy, including the Creative Industries Sector Deal, the digital is assuming increasing importance within research and innovation, as witnessed by the insertion of ‘Digital’ into the title of the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The 2018 DCMS Policy Paper Culture is Digital and the March 2019 UKRI Infrastructure Roadmap Progress Report highlight the importance of using digital technology, AI and machine learning to bring together dispersed collections, and to create research networks and shared platforms, to render resources visible and easily accessible to researchers and to the wider public. Understanding these developments and their impact across the whole range of our activities poses a challenge: in fine arts practice, urban planning and architecture, archaeological mapping and data presentation, for example, and in the curation and opening-up of archives and special collections.

In this context, the BSR has been considering how best to develop the research potential of our collections, consolidate and curate the work completed to date, and build connectivity and capacity in collaboration with cognate institutions and collections. Given the range of research activities and creative practices we support, we are keen to ensure we effectively integrate technology into our scholarly and artistic practice. For some time, members of the BSR Library and Archive team have been looking to develop a digital portal to host the material generated since 2002 (see below, section 4). The creation of the BSR Digital Collections website in 2009 began to make available online our unique material. More recently we have been working to identify the correct digital platform to integrate both our Digital Collections and our wider digital interface. To this end, staff have participated in workshops and conferences over the last twelve months (including the 2018 biennial Digital Humanities Congress at Sheffield), as we seek to establish a network of contacts within the digital humanities scholarly community, to share competencies and to move from consultation, conservation and specialist research to broader dynamic interactions with digital data. For an institution of our size, this aspect of networking and shared endeavour is vital. It is only by working collaboratively that we can understand how best to unlock the research potential of our holdings and to make the most of the huge opportunities presented by data-driven research and collaborative digital partnerships. Our aim is to make our special collections discoverable, accessible and usable through sustained curation and continued engagement with the enriching potential presented by innovation in the digital humanities.

2. Transition from Analogue to Digital

The BSR’s Archives had lain dormant for decades, and it was not until the 1980s that their value, particularly at that time of the unique photographic collections, was appreciated fully. The question was how to bring these to the attention not only of scholars and researchers, but also a more general public. With the limited resources available at the time, collaboration was essential. We worked with many Italian institutions, which generously funded our projects and the teams of researchers who studied the material, and together we embarked on a journey that lasted over 30 years.

Thomas Ashby,1 the first student (in 1901) of the newly founded BSR and subsequently its Director from 1906 to 1925, left a remarkable collection of over 8,000 negatives and prints (glued into albums) that he took, predominantly in Italy — documentary evidence vital for his research, particularly on the archaeology and topography of Lazio, Abruzzo, Sardinia and Sicily. Ashby’s seminal work on the Roman Campagna (1927), still much cited today, included just a small selection of his photographs as illustrations. The Roman Campagna (the area of Lazio north of Rome) was the subject of our first project. In the 1980s, the only possibility open to us for disseminating the many images was through publications and exhibitions. Over 70 years had passed since the photographs had been taken, and the area around Rome had been transformed, or devastated, depending on your point of view. New excavations and research, including the BSR’s own ground-breaking archaeological survey of the 1950s and ’60s in this area, were vital for a team of archaeologists who studied the photographs in the light of these developments. An exhibition was held at the BSR in 1986, attracting a wide and varied audience; and a catalogue was published (Campagna Romana 1986), the launch of the British School at Rome Archive series.

Our aim, as noted above, was to open-up our Archives, to release these unique collections from their locked cupboards; but it is ironic that the moment hitherto unknown collections are freely available and in the public domain, the interest of researchers and scholars focuses on what has not been published. Our second catalogue and exhibition of Ashby’s photographs, this time of the city of Rome (Archeologia a Roma 1989), therefore, contains all the relevant images from his collection relating to the excavation of the Roman Forum in Rome at the beginning of the twentieth century, as well as transcriptions of his copious, often scribbled, notes, written on the backs of envelopes. The third publication concentrated on Ashby’s photographs of Lazio (Lazio 1994), and the related exhibition was so successful that it travelled around the region for many years. It was not only archaeologists and specialists who were drawn to the images, but also the inhabitants of these towns and villages, curious to see how dramatically and drastically the countryside had changed since their grandparents’ day, not so long ago, and parents with their children searching for the family home. It felt as if we were returning these images to their rightful owners.

Our horizons broadened, and the BSR Archive series of publications began to include new collections, subjects and types of materials. In a BSR publication of 1992, Rome Scholar in Architecture Hugh Petter narrated the extraordinary story of our building, designed by the architect Edwin Lutyens, constructed during WWI and completed in 1916,including reproductions of the original architectural drawings (Petter 1992) (Figure 2). The photographs of Sardinia taken by a Dominican father, Peter Paul Mackey, at the end of the nineteenth century, as he explored the island on a donkey, provided material for another volume (Crawford, Romagnino and Zucca 2000).

Figure 2: The BSR under construction between 1912 and 1916

Our first encounter with the digital world began in the late 1990s, when a digitisation campaign of the Thomas Ashby collection was proposed by the external institution that at that time held the negatives on permanent loan (but which have now been returned to the BSR). This was the beginning of a steep learning curve, as the technology used to convert the photographic material into digital format was Photo Cd Kodak, which quickly became obsolete. The realities of digitisation became clear. It is not, as many people erroneously believe, the quick and simple answer to problems of dissemination, conservation and longevity. The long-term preservation of objects has a cost (conservation material for storage, climate control, space, etc), and the conservation of digital data is more complicated and costly (digital repository, hosting and maintenance, quality control, upgrading of hardware and software, inbuilt obsolescence). The quality of the ’90s digital images (available on URBiS) is not acceptable today, and funding must be found gradually to re-digitise the whole of the Ashby collection (and many grants today will not cover the costs of digitisation).

The pivotal years for our transition to the digital domain were 2002 to 2009, when we received two generous grants from The Getty Foundation, funding the cataloguing of 15,000 images and culminating in the launch of the BSR Digital Collections website. The first publication illustrated with digital images dates to 2009, and was dedicated to Ashby’s photographs of Roman aqueducts in Lazio (Le Pera Buranelli and Turchetti 2007). For the first time large (30 × 40 cm) digital carbon prints were displayed in the accompanying exhibition — a mode of display that subsequently has become our preferred model. This was followed by volume 8 in the BSR Archive series, which made available the research of Robert Coates-Stephens (BSR Cary Fellow) on Father Mackey’s photographs of Rome, taken between 1890 and 1901,revealing a surprisingly industrial cityscape (Coates-Stephens 2009).

A collaboration with the University of Salento and the Region of Campania resulted in research on a unique collection of photographs, unknown outside the BSR, taken by Robert Gardner, Craven Fellow at the BSR in 1912–13, who accompanied Thomas Ashby on a cycling trip to explore the Via Appia from Benevento to Brindisi. Two volumes were published exactly 100 years after the epic journey (Ceraudo 2012; Castrianni and Ceraudo 2013).

The two latest projects, presenting Ashby’s photographs of Abruzzo and Sardinia,have taken a qualitative leap in terms of production and printing (Tordone 2011; Manca di Mores 2014; Manca di Mores 2018). In addition, the public outreach and impact has increased notably, with 40,000 visitors recorded as the exhibition arising from the first project toured the region of Abruzzo, which Ashby visited at least six times between 1901 and 1923. An inhabitant of the town of L’Aquila visited the exhibition and recognised a young boy, staring out of a photograph, as his father, an identification confirmed by his siblings. This is the only photograph of the boy, who had probably never seen a camera before. In Sardinia, the Director of the Museo Nazionale Archeologico ed Etnografico Sanna in Sassari, which hosted the exhibition, reported that the number of visitors to the museum whilst the exhibition was on had increased by 24% compared to the previous year.

3. State of the Art

Over the last decade, digital humanities undoubtedly has emergedas a field serving many disciplines, and has become an important element in research practice, as shown by the ever-increasing numbers of scholars, centres, projects and funding opportunities that are embedding digital technology as a natural and necessary means to achieving their aims and objectives (Monella 2012; Gold and Klein 2016; Kelly 2017; Weston, Carbé and Baldini 2019). Digital humanities projects already play an important role in the BSR’s research landscape, and we are building momentum through collaboration with other institutions based in the UK, Italy and the Commonwealth on a number of past and on-going projects.2 Since 2015, the BSR Library and Archive’s mission has been not only to facilitate research but, very importantly, to actively generate research on its special collections. More recently, the emphasis has shifted also to prioritising funded collaborative research projects with UK and Commonwealth Higher Education Institutions.

Given the role played by libraries and archives in facilitating access to their resources through online public catalogues (OPACs), meta catalogues and digital libraries, it is logical and imperative that research projects envisaging the use or development of digital tools should grow around those very institutions that are responsible for access to and the preservation of collections that are deemed essential for research.

In order to achieve that goal, it is essential that work on the ‘raw materials’, such as rare book collections, archival documents and photographic collections, is carried out with a view to creating structured and content-rich datasets to facilitate the use and implementation of digital humanities tools and methods. The importance of the quality of digitisation and metadata, which will unquestionably affect the quality of the research, cannot be overemphasised.

As far as the BSR is concerned, it is a matter of exploring and understanding how we can help build institutional capacity in the field of digital humanities, whilst ensuring that matters of long-term sustainability and accessibility (both directly to these resources, as well as projects generated from them), are always taken into account.

To what extent can a small institution such as the BSR — with a renowned position for over a century of UK scholarship abroad — support the development of a digital humanities function, in order to unlock the great potential of its special collections?

4. Towards the Creation of a Digital Humanities Portal

As noted previously, over the past fifteen years the BSR has developed a significant portfolio of digitisation and cataloguing projects, and has been successful in securing external funding. This led, in 2009, to the creation of a digital library conceived and built on digital objects and, consequently, quite different in its scope to an OPAC. The BSR Digital Collections website has brought the BSR’s unique historic collections to a global audience, providing access to photographic material, as well as a selection of maps, drawings and engravings from our special collections. Some figures will sum up our achievements so far: 30,384 records available in MARC21 on our ILS system and accessible on the URBiS meta catalogue; a total of 27,260 digital objects, of which 15,170 are published on BSR Digital Collections website.3 During the first half of the BSR academic year (August 2018 to January 2019), there were some 17,500 unique visitors to this website, making over 1 million hits from over 50 countries; with the average length of visit being nearly 14 minutes.

The website was designed not only to satisfy the needs of an audience that was increasingly demanding access to visual material in digital format, but also to ensure the long-term preservation of technical and descriptive metadata. From the outset, we focused on the quality of data content, structure and format, adopting international standards for cataloguing and publishing digital content to ensure interoperability with other projects.4 High-quality metadata were considered essential to facilitate the implementation of research methodologies.

Alongside the BSR Digital Collections website, the BSR Library and Archive has been involved in various research projects, two of which have entailed the creation of a dedicated website and the adoption of a crowdsourcing platform: the John Marshall Archive and the William Gell Projects.

The John Marshall Archive is an example of an international collaborative research project generated by the BSR, based on material held by the BSR since the 1920s. John Marshall was a dealer in antiquities living in Rome at the beginning of the twentieth century, and represented both the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He frequented the BSR, and left his archive to us in his will. The archive includes photographs of artefacts that were offered to him for sale (Figure 3), his hand-written card catalogue (annotated and organised thematically), with information regarding each object, and his correspondence. A team of international scholars and curators have been working on this provenance project, which seeks to identify the current whereabouts of the artefacts, as well as describing his life and circle of associates, and examining the wider culture of trading in antiquities at the start of the twentieth century.

Figure 3: A photograph from the John Marshall Archive

The website, which is based on a LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySql, Php) platform, has been designed to show and maintain the complex relationships between each component of the archive, whether photographs, catalogue cards or his correspondence. The digital representation of this archive includes 861 catalogue cards, nearly 3,000 photographs, and 460 transcriptions of his correspondence and personal notes. Users can browse the archival items by material/technique, typology/function and subject matter/theme, or search by keywords or through an advance search form. This resource is currently accessible only to the research team, pending publication of a volume in the British School at Rome Studies series with Cambridge University Press, at which point it will be launched to the wider research community.5

The ambitious aim of a second research project seeks to reunite a dispersed corpus virtually. William Gell was a British topographer and archaeologist who lived in Italy at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Wallace-Hadrill 2006; Riccio 2013). Gell was born at Hopton Hall in Derbyshire, and educated at Derby School and Emmanuel College, Cambridge. In 1797 a book he had written and illustrated on a tour he had made of the Lake District was published (Gell 2000). From 1801 he travelled extensively in Greece, Asia Minor and, subsequently, Italy. Gell moved permanently to Italy in 1820, and lived in Rome and Naples until his death in 1836.

The BSR holds seven of his notebooks, which were apparently found by Thomas Ashby, former Director of the BSR, on a market stall in Naples in the 1920s. Gell must have filled innumerable notebooks preparing his volume The Topography of Rome and its Vicinity, published in 1834: Ashby managed to find three of them, dated 1826–7, 1828 and 1829–30. They are all small, 14 × 20 cm.

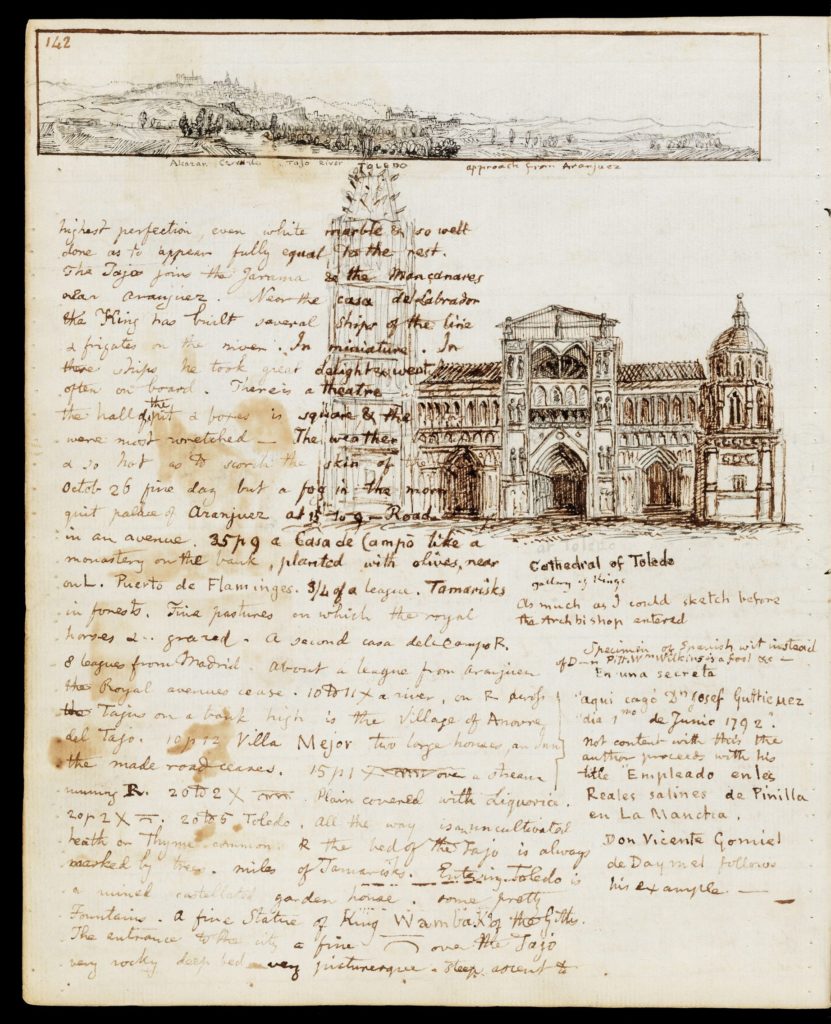

Another of the notebooks is particularly interesting. More a book than a notebook, it has 213 pages, is larger than the others (18 × 23 cm), and is a detailed description of Gell’s trip to Spain in 1808 and Portugal in 1810, complete with sketches, topographical drawings, watercolours and even music (Figure 4).

Figure 4: A page from William Gell’s notebook on Spain and Portugal

Numerous other Gell notebooks are held in library and museum collections around the world: Athens, Los Angeles, Oxford, Paris and Naples. Initially we sought to coordinate a joint research project involving all the other stakeholders. Although there was a lot of interest, nothing happened. We then decided to start by publishing one of our notebooks. We came across the Getty Scholar’s Workspace Platform and, in collaboration with the Getty Research Institute (who invited us to Los Angeles and encouraged us to use the platform), we initiated the project on our own. For this project, in collaboration with Professor Roey Sweet (University of Leicester), we selected the sketchbook of landscapes and monuments in northern England and Scotland. The volume is leather-bound, and measures 18 × 11 cm. The sketchbook has been restored, digitised and researched. The drawings have been individually catalogued, and the sketchbook will be published online, with peer reviewed accompanying essays and bibliography, using the Getty’s open source platform.

The BSR Digital Collections website is now nine years old, and needs refreshing, although its functionalities still prove effective and the architecture is robust. Moreover, the ever-increasing engagement of our collections in research projects requiring digital outputs and seeking to use digital tools to represent and display datasets, raises questions for us on how to manage the transition from a dispersed set of digital platforms to an homogenous digital environment, where these resources are all framed into a meaningful narrative.While it is clear that a more up-to-date platform is needed to unite and manage our digital collections, as well as facilitate our own research projects, it is more difficult to understand how we can create a space within a single portal to allow us to develop, promote and sustain effectively our digital humanities strategy.

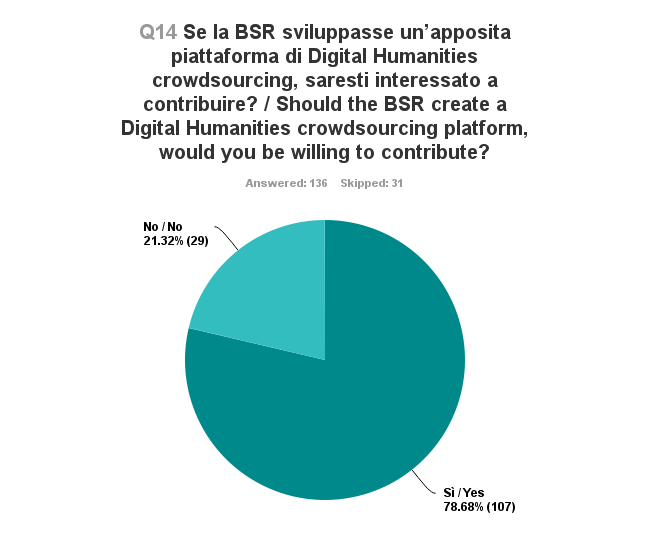

A survey conducted in 2017 gave us some pointers on how we should develop our digital capacity. The survey tool was a Survey Monkey questionnaire asking multiple choice and short answer questions that were developed around three areas: interviewees’ background and interests; use of our current Digital Collections website; and specific questions on crowdsourcing platforms and other forms of participatory research. The total number of respondents was 167 (although not all answered all questions).

47% of our survey respondents were living in English speaking countries; more than 90% were aged over 31; and more than 50% were university-related people. Although the interest shown in the visual material (photographs, engravings, postcards, etc.)was strong, the demand for other resources — such as archival documents, museum objects, as well as podcasts and videos of BSR workshops and lectures —demonstrates that these records also are important for research purposes. A high percentage (88%) of the survey respondents emphasised the need for a transparent and user-friendly notice relating to the copyright licences of the material (i.e. Creative Commons), and the respondents were generally well disposed towards the implementation of crowdsourcing platforms, such as transcription tools (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Responses to a survey question on interest in contributing to a crowdsourcing platform

Most of the interviewees expressed an interest in a digital humanities portal that includes completed projects. Some 64% of respondents expressed an interest in contributing to the development of content through a crowdsourcing platform.

4. Conclusions

Although we have been constantly mindful to ensure that the long-term development and curation of our digital projects are the responsibility of the institution, rather than dependent on a single individual or single grant, we are aware thata clear digital humanities strategy is needed to allow us to develop our digital initiatives further. Such a strategy will allow us to sustain and develop our digital initiatives through the integration of our disparate projects into a single portal, which is also affordable and sustainable.

This will involve considering many questions and issues that were raised at the conference at which this paper was originally given:

- How can we engage more effectively with our audience, providing more dynamic access to our online collections, taking into account recent developments in web technologies?

- How do we reconcile being a small institution with limited financial resources with the potential held in our special collections and archival holdings?

- How do we best make the transition from ad hoc activity to a strategic digital research programme?

- How do we broker collaborations that are bidirectional and reciprocal, and enable us to build capacity?

- How do we best ensure that our staff has the necessary level of technical knowledge and know-how to manage and deliver an ambitious programme?

Only by addressing and answering these questions will we be able to unlock and realise the incredible research potential of the BSR’s special collections, and make the most of the huge opportunities presented by innovations in the field of digital humanities.

5. References

Archeologia a Roma (1989). Archeologia a Roma nelle fotografie di Thomas Ashby, 1891–1930 (British School at Rome Archive 2). Naples: Electa.

Ashby, T. (1927) The Roman Campagna in Classical Times. London: Benn.

Campagna Romana (1986). Thomas Ashby: un archeologo fotografa la campagna romana tra ‘800 e ‘900 (British School at Rome Archive 1). Rome: De Luca.

Castrianni, L. and Ceraudo, G. (2013) (eds) La Regina Viarum e la via Traiana: da Benevento a Brindisi nelle foto della collezione Gardner (British School at Rome Archive 11). Grottaminarda: Delta3 Edizioni.

Ceraudo, G. (2012) (ed.) Lungo l’Appia e la Traiana: le fotografie di Robert Gardner in viaggio con Thomas Ashby nel territorio di Beneventum agli inizi del Novecento (British School at Rome Archive 10). Grottaminarda: Delta3 Edizioni.

CIPRO 2001, CIPRO. [online] Available at: <http://fmdb.biblhertz.it/cipro/default.htm> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

CLAROS 2000, CLAROS, the world of art in the semantic web. [online] Available at: <http://explore.clarosnet.org/XDB/ASP/clarosHome/about.html> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

Coates-Stephens, R. (2009) Immagini e Memoria: Rome in the Photographs of Father Peter Paul Mackey, 1890–1901 (British School at Rome Archive 8). London: British School at Rome.

COPAC UK 1996, COPAC. [online] Available at: <https://copac.jisc.ac.uk/> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

Crawford, A., Romagnino A. and Zucca, R. (2000) Immagini dal passato: la Sardegna archeologica di fine Ottocento nelle fotografie inedite del padre domenicano inglese Peter Paul Mackey (British School at Rome Archive 5). Sassari: Delfino.

EAGLE 2013, Europeana EAGLE Project. [online] Available at: <https://www.eagle-network.eu/> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

Gell, W. (2000) A Tour in the Lakes, 1797, edited by W. Rollinson. Otley: Smith Settle.

THE GETTY, (2016). Getty Scholars’ Workspace. [online] Available at: <http://www.getty.edu/research/scholars/digital_art_history/getty_scholars_workspace/index.html> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

Giovenco, A. and Di Iorio, A. (2012) La pubblicazione in rete delle collezioni digitali della Biblioteca e dell’Archivio della British School at Rome. In B. Fabian (ed.), Immagini e memoria: gli archivi fotografici di istituzioni culturali della città di Roma: 183–91. Rome: Gangemi.

Gold, M. and Klein, L. (2016) Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

GOV.UK 2017, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, Industry Sector Deals. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/industry-sector-deals [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

GOV.UK 2018, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy and Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Industrial Strategy: Creative Industries Sector Deal. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/creative-industries-sector-deal [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

GOV.UK 2018, Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Policy Paper Culture is Digital.[online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/culture-is-digital/culture-is-digital [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

Hodges, R. (2000) Visions of Rome: Thomas Ashby, Archaeologist. London: British School at Rome.

IRC 2005, Inscriptions of Roman Cyrenaica. [online] Available at: <https://ircyr.kcl.ac.uk> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

IRT 2009, Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania. [online] Available at: <http://inslib.kcl.ac.uk/irt2009/> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

Kelly, J.M. (2017) Reading the Grand Tour at a distance: archives and datasets in digital history. The American Historical Review122 (2): 451–63.

Lazio (1994). Il Lazio di Thomas Ashby, 1891–1930 (British School at Rome Archive 4). Rome: Palombi.

Le Pera Buranelli, S. and Turchetti, R. (2003) (eds) Sulla Via Appia da Roma a Brindisi: le fotografie di Thomas Ashby, 1891–1925 (British School at Rome Archive 6). Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider.

Le Pera Buranelli, S. and Turchetti, R. (2007) (eds) I giganti dell’acqua: acquedotti romani del Lazio nelle fotografie di Thomas Ashby (1892–1925) (British School at Rome Archive 7). Rome: Palombi.

Manca di Mores, G. (2014) (ed.) La Sardegna di Thomas Ashby: paesaggi, archeologia, comunità: fotografie 1906–1912 (British School at Rome Archive 12). Sassari: Delfino.

Manca di Mores, G. (2018) (ed.) Thomas Ashby’s Sardinia: Landscapes Archaeology Communities. Photographs 1906–1912 (British School at Rome Archive 12). Sassari: Delfino.

Monella, P. (2012) Are tools all we need? Digital humanities in the time of its institutionalisation. Testo e senso 13. [online]Available at: <http://testoesenso.it/article/view/124> [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Petter, H. (1992) Lutyens in Italy: the Building of the British School at Rome (British School at Rome Archive 3). Rome: British School at Rome.

Riccio, B. (2013) (ed.) William Gell, archeologo, viaggiatore e cortigiano: un inglese nella Roma della Restaurazione. Rome: Gangemi.

Tordone, V. (2011) (ed.) Thomas Ashby: viaggi in Abruzzo, 1901–1923 (British School at Rome Archive 9). Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale.

UK Research and Innovation 2019, UKRI Infrastructure Roadmap Progress Report. [online] Available at: https://www.ukri.org/files/infrastructure/progress-report-final-march-2019-low-res-pdf/[Accessed 8 Mar. 2019].

URBiS 2015, URBiS Library Network.[online] Available at: <http://www.urbis-libnet.org/vufind/> [Accessed 7 Feb. 2019].

Wallace-Hadrill, A. (2001) The British School at Rome: One Hundred Years. London: British School at Rome.

Wallace-Hadrill, A. (2006) Roman topography and the prism of Sir William Gell. In L. Haselberger and J. Humphrey (eds),Imaging Ancient Rome: Documentation, Visualization, Imagination: Proceedings of the Third Williams Symposium on Classical Architecture (Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 61): 285–96. Portsmouth, R.I.: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

Weston, P., Carbé, E. and Baldini, P. (2019) Hold it all together: a case study in quality control for born-digital archiving. QQML 5 (3): 695–710. Available at: http://www.qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/352 [Accessed 25 February 2019].

Wiseman, T.P. (1990) A Short History of the British School at Rome. London: British School at Rome.

- For a biography of Thomas Ashby, see Hodges (2000); for his role in the development of the BSR, see the catalogues of the exhibitions of Ashby’s photographs: Campagna Romana (1986); Archeologia a Roma (1989); Lazio (1994); Le Pera Buranelli and Turchetti (2003); Le Pera Buranelli and Turchetti (2007); Tordone (2011); Manca di Mores (2014; 2018).

- Our data have been shared with the following projects: CIPRO (Catalogo illustrato delle piane di Roma online), Bibliotheca Hertziana, Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte; IRC (Inscriptions of Roman Cyrenaica) and IRT (Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania), Centre for Computing in the Humanities, King’s College, London; CLAROS (Classical Art Research Online Research Services), Oxford University; EAGLE (Europeana network of Ancient Greek and Latin Epigraphy); COPAC UK Union catalogue.

- For a more extensive description of the project, see Giovenco and Di Iorio (2012).

- We have always adopted international standards for cataloguing (Marc21, METS, MODS, DC, NISO MIX in XML format), used open source solutions for our website to allow easy sharing of data, and used a professional photographer to carry out digitisation to the highest standard with associated metadata.

- An international team of scholars has undertaken research on the material. A one-day conference was held at the BSR, and a publication is in preparation, The Classical Past for Sale. John Marshall and the Trade of Antiquities in Early Twentieth Century Europe.