by Mike Bowman

1. Introduction

These days we take it for granted that works of art have titles, and practices around the giving, presenting and interpretation of titles have been institutionalised within the art world. However, this was not always the case. Up to the end of the eighteenth century, as the scholar Ruth Yeazell (2015) has argued, references to paintings such as the entries in exhibition and sales catalogues were predominantly descriptive, informing the reader as to the subject matter of the painting, and classificatory, identifying the genre or type of work. Works of literature had titles, and the inscriptions beneath the images on prints were also described as such, but catalogue entries were neither used nor understood as titles. Based in part upon the earliest appearance of the word ‘titre’, in her reading Yeazell tentatively identifies the 1790s as the decade in which our modern notion of the title of a picture first started to gain some traction in France. The overriding question that shapes this paper is that of understanding how, from those beginnings, titling for new and original paintings emerged in the nineteenth-century French art world as a practice, and as a concept to describe that practice.

The focus of my paper is the Paris Fine Art Salon. A state-sponsored event, the Salon ran for up to eight weeks on a yearly or two-yearly cycle. It was a huge event, and for most of the nineteenth century was the dominant institution in France for showing new art. Without showing at the Salon it was very hard to have a career as a professional artist in Paris. Each Salon exhibition was accompanied by an official catalogue which provided the names and addresses of the artists, and a listing and explication of the works on show. Although editorial control of the catalogue rested with the Salon administration, artists were largely responsible for the text of their entries. The Salon catalogues therefore provide a unique, continuous record of the language used by artists to refer to new and original works of art during my period of interest. My quantitative analysis of the emergence of titling was based upon a database I created from a random sample of the entries made in the Salon catalogues. To complement my analysis of catalogue entries I also assembled a sample of critical writing in electronic format. Salon criticism shows how those entries were understood, for instance in referring to an entry as the title of the work in question.

2. Data Sources and Methodology

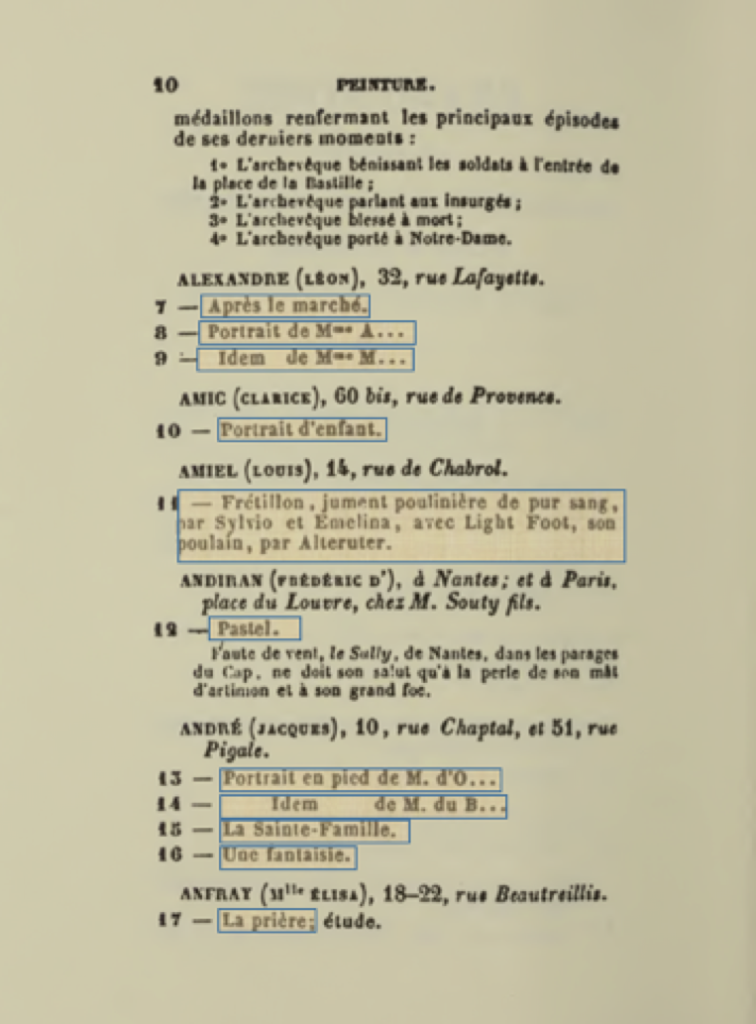

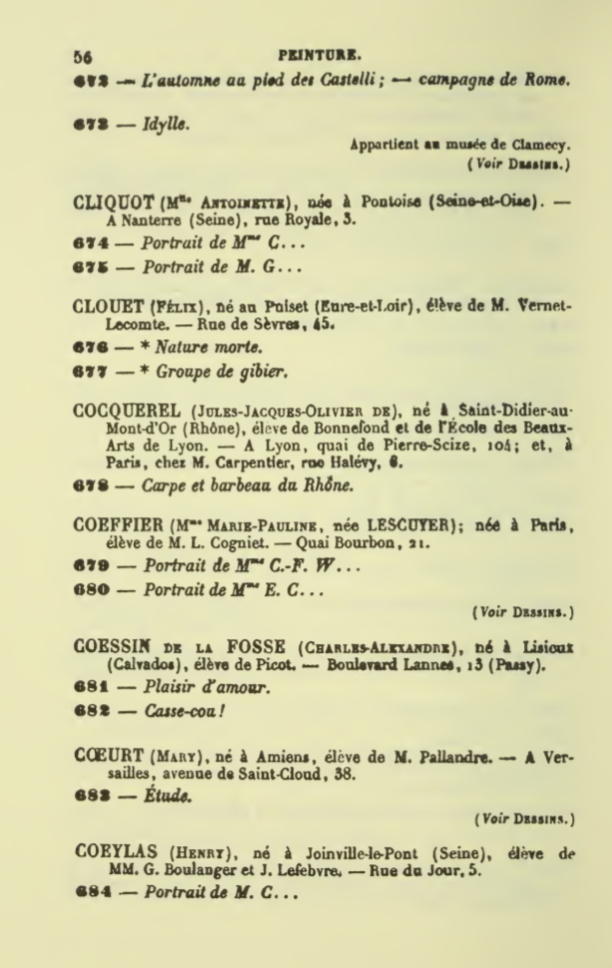

I took a sampling approach to the creation of my database, as an effective way of investigating the long-term trends in the use of language in the catalogue, and also as I needed to manually process and categorize each entry. The catalogues are available through the Internet Archive; however, the format of entries and the quality of the scanning varies considerably from year to year, and so my database had to be compiled entirely by hand. For each decade I took a random selection of 1,000 entries from the section of the catalogue used to list the paintings on display at the Salon, which included not only oil paintings but works in other media such as watercolour, pastel and gouache, as well as drawings and sketches. I entered into my database the year of the Salon, the catalogue number of the work, a transcription of the text of the main entry (which is the text highlighted on the extract from the catalogue for 1824 given in Figure 1), the type of work (watercolour, drawing etc.), and the number of objects under the entry (there are four works listed under the same catalogue number with the entry at the top of Figure 1, and one work listed under all of the other entries). I added a flag for whether or not the entry included a detailed explication in addition to the main entry. When present, as with entry 12 in Figure 1, this part of the catalogue entry was typically used to give a literary reference or quotation, or detailed information about the subject of the painting, as might be the case with a biblical or battle scene. I also classified each entry with a generic category depending upon the subject indicated. The categories were: mythological, religious or historical subjects; everyday genre scenes; landscapes; portraits; still-lifes; and not stated or other. The relative popularity of different genres changed substantially during the course of the nineteenth century, and classifying each entry that way enabled me to control for those changes when investigating the trends in language use.

I started my database from the 1790s, taking my lead from Yeazell, but also as this was the first decade in which the Salon was opened up to all artists following the 1789 Revolution. In my first pass through the data I ended in the 1870s, as the last decade in which the Salon remained the dominant institution for showing new art. In the end I did not have to deviate from this choice and so my database ran from the 1790s to the 1870s, and included 9,000 entries.

Figure 1: Extract from the catalogue for the Salon of 1824 with the main part of each entry highlighted

To complement my analysis of catalogue entries, I also assembled a sample of critical writing on the Salon in electronic format, to allow for key word searching and other analyses. Salon criticism was a recognised literary genre in the French art world and critical reputations were often made through Salon reviews. At any one time there could be up to several hundred critics reviewing the Salon. However, the number of reviews available in electronic format through resources such as the Bibliothéque Nationale de France’s electronic library and Google Books is much more limited, and my sample extended to 98 reviews in total. Of these 98 documents, 80 were published in book format, mainly contemporary publications but also some compilations of earlier Salon reviews, and 18 were articles from newspapers and journals. Although this is only a very small proportion of all the Salon reviews produced, it extends across my period of interest, includes critics of all persuasions and was sufficient for my purposes of understanding the emergence of titling. As will be seen, the trends within this limited sample are so pronounced that they can be regarded as giving a strong indication of change in the French art world. It was not my aim to perform an independent analysis of critical writing, for which a much larger sample would have been required.

3. Critical Reviews of the Salon

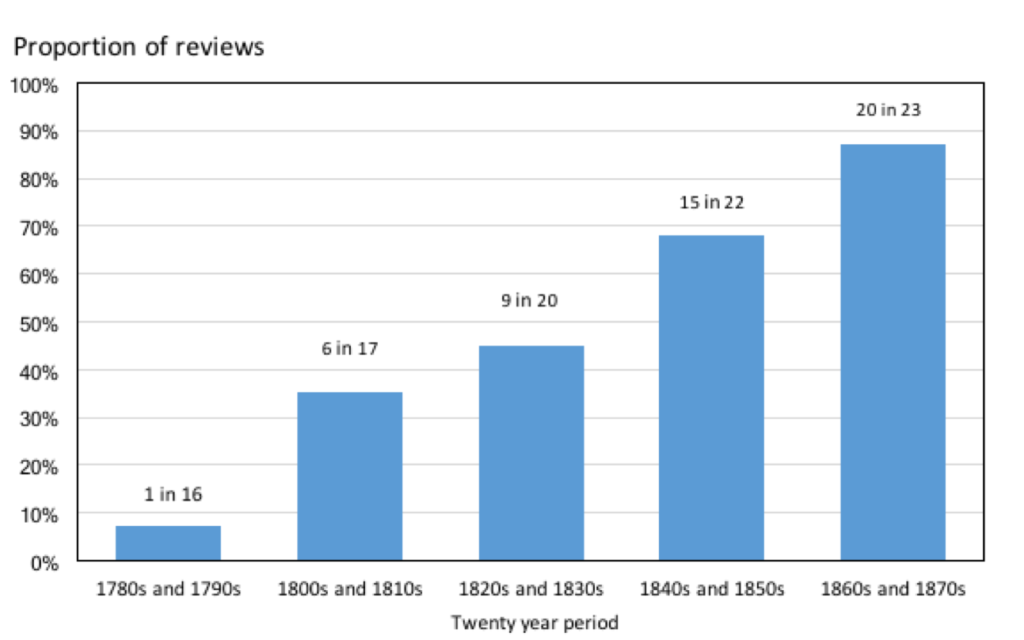

The simplest and most direct approach to measuring and mapping out the emergence of titling is to look at the use by critics of the noun ‘titre’ in the context of introducing or describing a painting, as well as related terms such as the verb ‘intituler’. I have presented that analysis in Figure 2, which looks in twenty-year periods at the proportions of critics using the term. As can be seen, critical use was very rare in the 1780s and 1790s. Of the 16 reviews in my sample from that period, only one, from 1798, referred to the titles of paintings on display at the Salon. The proportion of critics making some use of ‘titre’ or related terms rose steadily through the nineteenth century, and by the 1860s and 1870s it had become the norm. The writers of around 90% of Salon reviews during those two decades were conceptualising and writing about works of art as having titles, with those titles given by the entries in the catalogue or a close variant.

Figure 2: Proportion of critics using the term ‘titre’ or its equivalents in their Salon reviews, 1780s/1790s to 1860s/1870s

The textual contexts in which the word ‘titre’ was being used gives an understanding of how and why its use emerged and grew. Early occurrences were almost all in contexts where the critic uses the device of referring to a catalogue entry as a title to say something positive or negative about the work. In his review of a landscape at the Salon of 1798, whose entry in the catalogue was “View of the Normandy Coast”, François Doix (1798) refers to the painting as being presented under this “simple and modest title” (p. 18) before going on to praise the work as being neither simple nor modest. Critics who regarded the catalogue entry as a description of the subject of the painting were more limited in how they could use it. They could do little more than adopt the standard critical device of disapprobation common in the eighteenth and early-nineteenth century of saying of a work that it was ‘not an X’, where X was the subject indicated by the catalogue entry. Similarly, when the catalogue entry itself was used in the main body of the review, this was standardly to relate it to the subject of the painting, as in phrases such as ‘a painting representing Y’, or ‘Y is the subject of …’, with Y being the main catalogue entry or a close variant.

Over and above growth in the number of critics using this device as the nineteenth century progressed, it is likely that the increasing prevalence of this way of referring to catalogue entries would also have acted as a signal of linguistic practice and would have reinforced those trends and solidified and conventionalised their use. Indeed, by the 1860s and 1870s the use of the term ‘titre’ within critical language had changed significantly. Rather than using it as a device to say something about the painting, critics were using it far more commonly and simply as a standard way to name the work, as in ‘X’s painting entitled Y’, or in references to works being shown ‘under the title Y’, with Y being the main catalogue entry. By the 1870s, the understanding of catalogue entries as titles and the use of the term ‘titre’ and its equivalents to describe them had become an established and conventionalised part of critical discourse.

4. The Form and Content of Catalogue Entries

Changes in the language used by artists in their catalogue entries can also be interpreted in terms of the emergence of titling. However, as artists did not refer to or use entries elsewhere in the catalogue itself, this is not as straightforward as it is with reviewing critical language. It is also not a matter of looking at each entry and attempting to decide whether it is a title or not. The same piece of text could feature in a catalogue from the late eighteenth century, when it would not have been understood as a title, and one from the late-nineteenth, by which time it would most likely have been considered as such. Rather, it is a question of thinking about the functions that we associate with the title, and looking at how those functions became the dominant uses of catalogue entries as the sorts of use you might associate more with an understanding of entries as descriptive or classificatory defined. As the semiotician José Besa Cambrupi (2012) has argued, there are three basic functions which the title performs, and his categorisation can be applied productively to describe the changes in the form and content of catalogue entries associated with the adoption of titling.

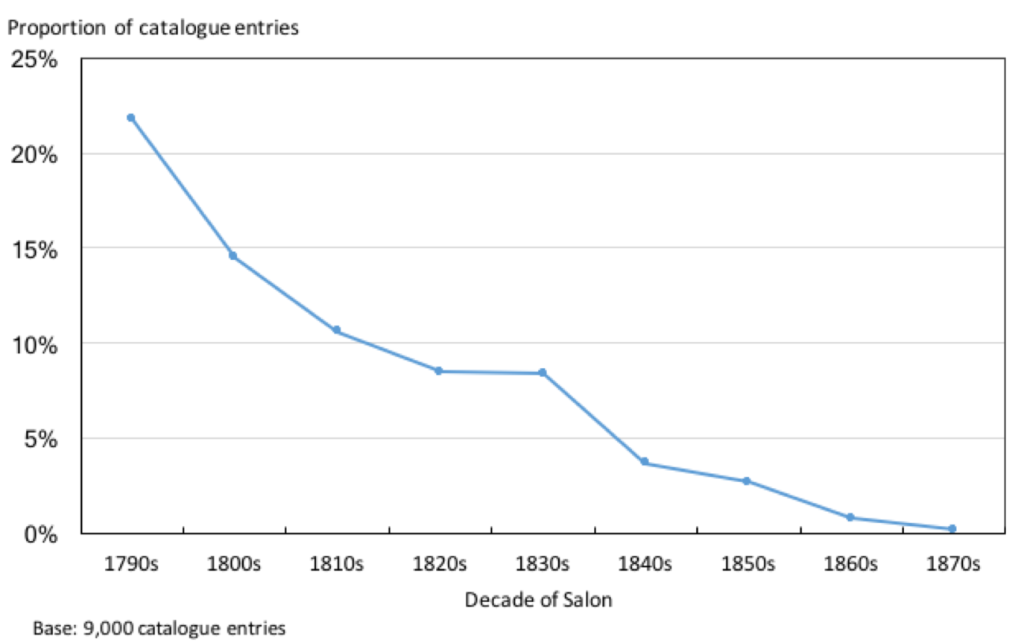

The first function of the title is that of naming. Titles are always names, and to name something is to individuate it. The adoption of this use of catalogue entries can be seen in the trend towards the individuation of those entries and of the objects to which they referred. I have presented that trend in Figure 3. As can be seen, in the 1790s over one in five catalogue entries related to more than one object, and there was then a rapid decline in such entries, such that by the 1870s effectively every painting on display at the Salon had its own individual entry.

Figure 3: Proportion of entries in the catalogues for the Paris Salon used to refer to more than one object, 1790s to 1870s

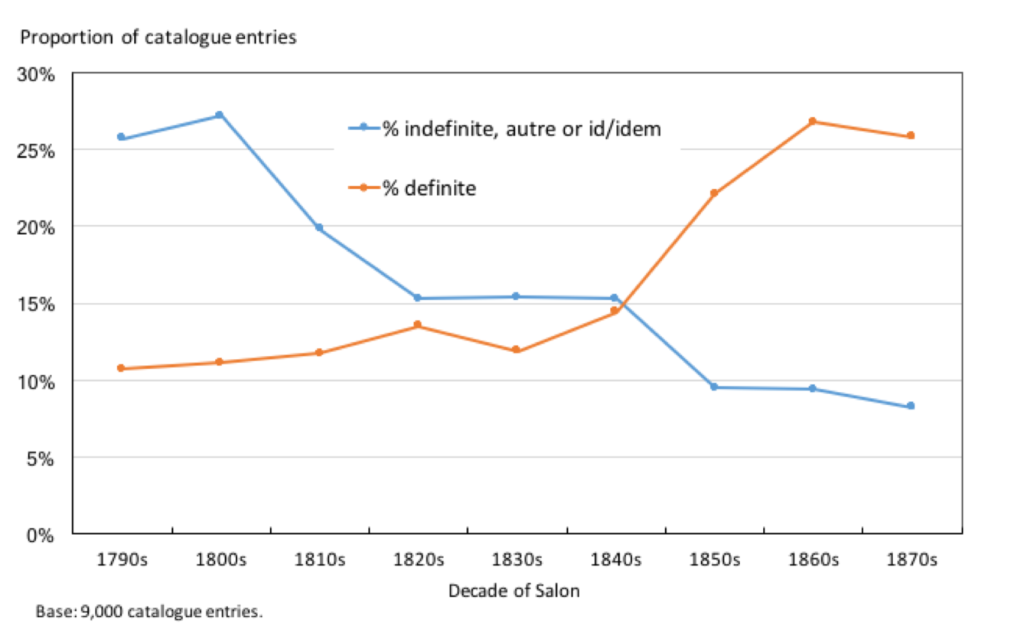

Additional evidence of the move towards individuation comes from the language used within catalogue entries. The basic function of the indefinite article is to classify. Artists also sometimes used the terms ‘autre’, ‘id’ or ‘idem’ in entries in the catalogue to indicate the same type of work or subject as the previous entry, and uses of these terms in such contexts are also signs of non-individuation in the sense that the entries are not complete in themselves. All three of these uses of language in catalogue entries, I would argue, can be interpreted as being most likely associated with the thinking of entries as descriptive or classificatory. Their use, as shown in Figure 4, declined substantially over the course of the nineteenth century, from featuring in over one entry in four in the 1790s and 1800s to fewer than one in ten in the 1870s.

Figure 4: Proportion of entries in the catalogues for the Paris Salon beginning with the indefinite article or including the terms ‘autre’, ‘id’ or ‘idem’, and proportion beginning with the definite article, 1790s to 1870s

On the other hand, the basic function of the definite article is to identify, and so growing use of the definite article at the start of entries can be read as indicative of greater individuation. This is also presented in Figure 4, which shows the increase in the use of the definite article in that way from featuring in around one in ten of catalogue entries in the 1790s to over one in four in the 1870s.

Standing back from the numbers, this process of individuation represented a wholesale shift in the way in which art works were conceived. By the 1870s, all of the paintings on display at the Salon were presented as objects in their own right and with their own names. To conceive of paintings in such terms would have been integral to the increasing commodification and commercialisation of the nineteenth-century French art world. To have a title, a fixed name attached to a painting, would also have supported the emergence of new forms of distribution and exchange of new works of art associated with that institutional change. Although the Salon retained its dominant position, as the century progressed market mechanisms came to play a greater role in the sale of art, and paintings changed hands more often.Professional dealers and the auction market for contemporary paintings grew in importance and influence, and the new generation of private collectors who emerged in the nineteenth century were much more likely to form and re-form their collections than the aristocratic and ecclesiastical patrons of the Old Regime. The assignment of a title to every object on display at the Salon would also have supported the commodification of all types of painting. As the art historian Nicholas Green (2009) has discussed, in the second half of the nineteenth century items which were previously regarded as secondary, such as the drawing and sketch, were increasingly sold and collected in their own right.

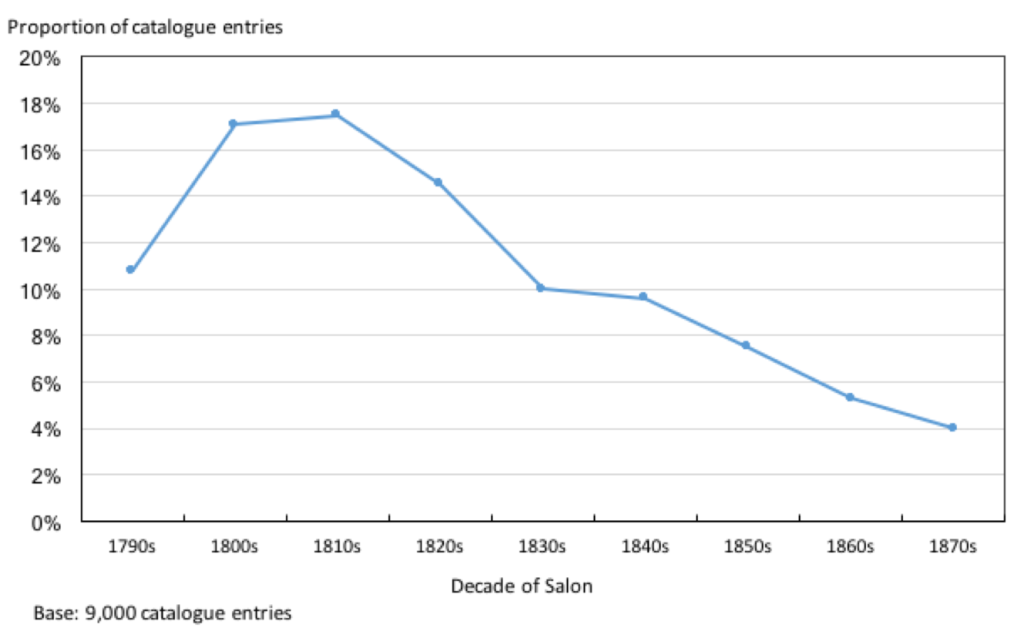

Titles are more than names, and the second function identified by Besa Cambrupi is that of providing a self-contained commentary on the work they identify. We can see the adoption of this way of understanding and using catalogue entries in the trend for artists to become much less likely to provide supplementary explication of the subject matter. It was the main entry itself which became the sole source of information from the artist to the reader of the catalogue. The declining trend in the use of supporting text is presented in Figure 5. What it shows is that the proportion of entries including supplementary text fell steadily from just under one in five in the 1800s and 1810s to 4% in the 1870s. Some of this would have been associated with the fall in popularity of historical subjects, as entries for such works were the most likely to have supplementary text, but it was a trend seen across all generic categories of entry. The lower figure for the 1790s than the next two decades reflects the popularity during that decade of pendants – pairs of paintings intended to go together. With pendants, the convention was to give detailed descriptions of the subject matter as the main catalogue entry rather than in supplementary text.

Figure 5: Proportion of entries in the catalogues for the Paris Salon with supporting explicative text, 1790s to 1870s

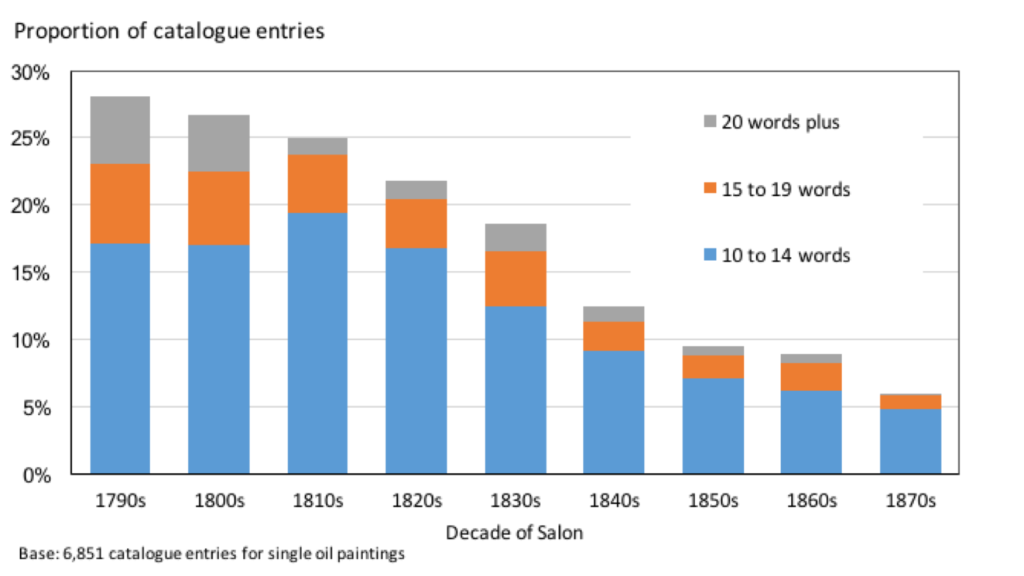

If we turn to the main entries for single oil paintings, then we can identify further trends in their form and content which I would interpret as being associated, at least in part, with using and thinking of them more as titles and less as descriptive or classificatory. Firstly, across all generic categories of entry during the course of the nineteenth century, artists largely abandoned the long descriptive entries often used in earlier periods to provide detail on the subject matter. In the 1790s and the early decades of the nineteenth century, it was quite common for landscape entries to give not only the place that the view was of itself, but also a specification of the place from which the view was taken. With still-life entries, artists might provide a long list of all of the objects and materials depicted so that the viewer could appreciate their technical virtuosity. Historical entries might give a long description of the actors and actions depicted. Figure 6 looks at the use of such ‘long’ entries, plotting the decline in the proportion of entries for single oil paintings of 10 words or more in length. As can be seen, over a quarter of entries for single oil paintings in the 1790s were long, but by the 1870s very long entries of 20 words or more had virtually disappeared from the catalogue, and there was very little use of entries of 10 to 19 words in length.

Figure 6: Proportion of all main entries for single oil paintings in the catalogues of the Paris Salon of length ten or more words, 1790s to 1870s

In addition to the decline in long descriptive entries, the use of short classificatory entries which simply gave the genre or type of work also fell away. They were common in the early nineteenth century, but their use then declined rapidly and there was much less use of such entries from the 1840s onwards.

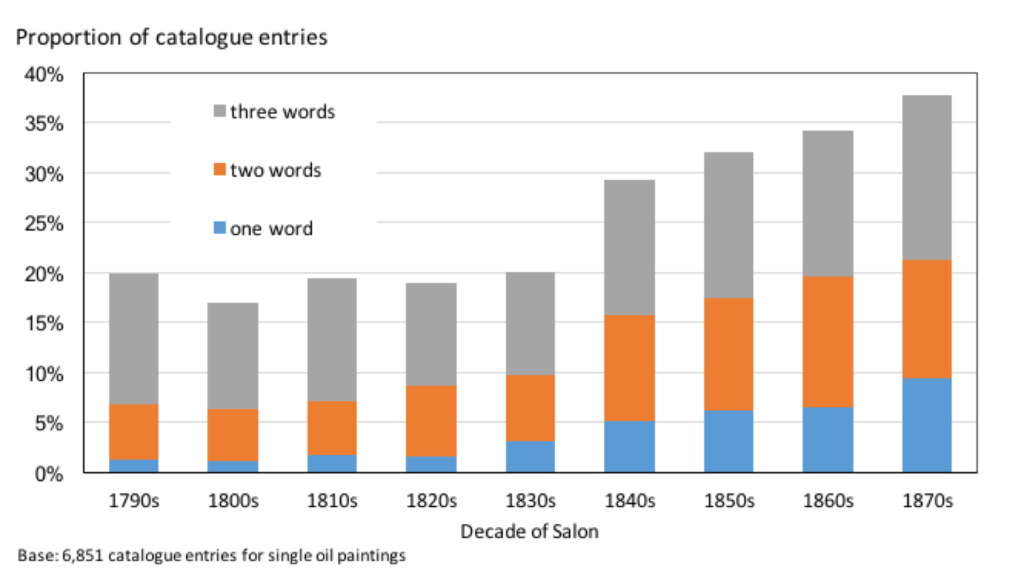

What replaced the long descriptive and short classificatory entries were, firstly, short entries which compressed meaning and commented on the work they named through succinctly directing the viewer’s attention toward the most important individuals, objects, locations or events depicted. Secondly, and at the same time, there was also an increase in the use of short entries which did not directly relate to the subject matter of the painting, but functioned to catch the reader’s attention through devices such as the use of punctuation, or through being idiomatic, humorous, sentimental, suggestive or simply puzzling in the way in which they alluded to the theme of the work. Two examples from the Salon of 1859 are “The Supreme Moment” and “Come on, don’t lie!”. Besa Cambrupi’s third function of the title is to seduce.

To quantify these trends, we can look at short entries of length three words or fewer. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, the growth in short directive, allusive or seductive entries was balanced out by the decline in short classificatory entries and, as can be seen from Figure 7, from the 1790s to the 1830s the proportion of entries which were up to three words in length was roughly constant. Growth in the former types of entry then exceeded the fall in the latter, and by the 1870s nearly 40% of entries for single oil paintings in the catalogue were these short directive, allusive or seductive entries.

Figure 7: Proportion of all main entries for single oil paintings in the catalogues of the Paris Salon of length three words or fewer, 1790s to 1870s

As I did with critical language, we can look to give an explanation of why this might have happened and how these practices were adopted and became the norm. Even if not always understood in the early-nineteenth century as titles, succinct allusive or eye-catching entries would have been of benefit to the artist in getting themselves noticed in the increasingly competitive environment of the Salon, and of the French art world more generally. In much the same way as the use of the term ‘titre’ became standardised in critical language, the increasing prevalence of these types of entry in the catalogue would have reinforced those trends and solidified and conventionalised their use.

To illustrate the overall effect of the changes I have interpreted as being associated with the emergence of titling, two extracts from the Salon catalogues of the early and late nineteenth century can be compared. As with the extract from 1806 presented in Figure 8, in the early decades of the nineteenth century the entries in the catalogue were quite heterogeneous, often not self-contained, and I would argue were in most cases seen as being descriptive or classificatory. By the 1870s, entries had become much more homogeneous in form and content, with, as can be seen from this extract from the catalogue for 1876, almost all items on display having their own self-contained and typically succinct entry. By that time entries were being used in ways which I interpret as indicating that they were predominantly being thought of as titles.

Figure 8: Extracts from the catalogues of the Paris Salon for 1806 and 1876

5. Summary and Conclusions

To summarise, what I have done in this paper is to look at the emergence of titling directly through the language used by critics, and indirectly through mapping out certain changes in the form and content of Salon catalogue entries. I have interpreted those changes as being most likely associated with a growth in thinking about and using those entries as titles – as names and as self-contained, typically succinct, commentaries on the work named, or as eye-catching devices – and a reduction in thinking of them as purely descriptive or classificatory.

Through the quantitative, systematic and sample-based approach that I have taken, it becomes possible to confirm the 1790s as the decade in which titling most likely began to emerge in France, to map out that process of practical and conceptual change, and to identify the 1870s as the decade by which it was largely complete. What this amounts to is a re-understanding of those entries and the way in which they were used, and a corrective to standard art historical thinking. Art historians typically write about the nineteenth century French art world as if paintings always had titles, and about catalogue entries as if they were always used and understood as such.

My analysis also matters to art history because, as I have argued, the adoption of titling was far more than a mere change in terminology. It delivered benefits to critics and artists. For the critic, referring to catalogue entries as titles enabled them to say something about the work of art which taking them as giving its subject did not. For the artist, they became less bound by the conventions which governed the use of entries as descriptive and classificatory, and they could use them strategically to distinguish their catalogue entries from those of other artists. Through individuating the art object and in providing a means to attract the potential buyer’s attention, the emergence of titling was also an integral part of the commercialisation and commodification of the nineteenth-century French art world.

6. References

Doix, FJA, 1798, Itineraire Critique du Salon de l’An VI, np, Paris, viewed 30 August 2018. <https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10523700b?rk=21459;2.png>.

Besa Cambrupi, J, 2002, Nouveaux actes semiotiques No 82: Les fonctions du titre, Presses Universitaires de Limoges, Limoges.

Green, N, 1987, ‘Dealing in Temperaments: Economic Transformation of the Artistic Field in France during the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century’, Art History, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 59-78.

Yeazell, RB, 2015, Picture Titles: How and Why Western Paintings Acquired Their Names, Princeton University Press, Princeton.