by Peter Blundell Jones

Cities are difficult targets for comprehensive study, not only because of their sheer size but because of their chronological layering. The medium used to represent or record them has a decisive effect on the results, and also on the extent to which the life of the city can be understood alongside its fabric. Literary accounts have a great appeal for the way they evoke personal experience but they are selective and subjective. Histories of actions and events can be equally evocative, but often remain frustratingly vague about precise locations and physical details. Maps and plans – especially the detailed late 19th century Ordnance Survey – seem suddenly to open up hitherto unknown worlds by revealing the sizes and relations of things, but we too often forget how restricted we are by the map-makers’ conventions, which tidy things up and leave things out. Limited to two dimensions and giving priority to the ground plane, maps also struggle adequately to show topography, and remain dumb on the question of relative building heights. Sketches and photographs give three-dimensional information, but sporadically and always from a chosen standpoint. The medium that provides the most complete information is probably the physical model, but it has to be to a limited scale and to portray the city at a fixed time, and it says little of the life of those involved. Computer models offer potentially more information and may theoretically offer chronological variations, but they have to be viewed on screens of limited resolution and in monocular mode, while movement of the viewpoint is cumbersome.

Grasping the past

The Sheffield Urban Study of 1998-2000 started with a consensus among the staff at the School of Architecture that the context of buildings is important, and that every designer of a new one should know the history of the site where it is to be built. This should help an understanding of how the place was formed and what it means, whatever use is made of such information subsequently in the design. We were also concerned with the more general questions of what constitutes a city, how cities might work today, and how buildings might (or might not) be integrated within them. Again, the current situation is only comprehensible with some understanding of the past, with an idea of how a city grew and how its past states contrast with how it is today. To understand an urban context more is needed than a peremptory glance at some old maps, but practising architects seldom have time for deep and extensive research, and many are ill-equipped to do it. Architectural students in the fifth year of their course, on the other hand, have at least the time if not all the skill, and where their skill is lacking it can be developed as part of their training. On one level this is a question of developing perception and understanding, of knowing what to look for and how to look, but it is also a question of learning how to use maps and archives, and of getting familiar with the kinds of things that can be found in them.

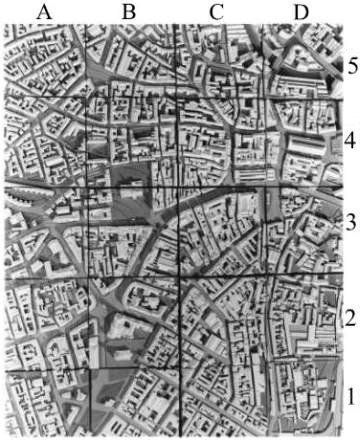

How does one study a city systematically? We decided to try to base our work around a physical model of the whole central area of Sheffield as it was in 1900. This date finds the city at its industrial height and the peak of its wealth, before the depredations of war, redevelopment, and the collapse of heavy industry. The date is late enough for accurate maps and photography, yet early enough to show many original features missing today. When we undertook the study, it marked the passage of a century, coinciding pertinently with the millennium. Ninety five students took part in the first part of the study over a period of four weeks, and we divided them into groups of four or five. A consequent division of the work was needed, so we imposed on the plan of the city a north/south and east/west grid. A one in four subdivision of the current Ordnance Survey grid produced 20 squares with a side-length of 200 metres on the ground. At a scale of 1:500 this gives a piece of model 40 cm2, and a whole model of the city centre 2.0 metres by 1.6. The scale of 1:500 is just large enough to show the forms of individual buildings and even chimneys, but without in most cases including such details as door and window openings. Co-tutors Alan Williams and Jo Lintonbon, then involved in PhD studies of Sheffield, constructed investigative prototypes to test the scale and to establish co-ordinated modelling methods. They also deduced the contour information from modern maps, so that the layered base of each grid-square could be prepared before the streets and buildings were imposed. The grey model of contours alone was temporarily assembled at an intermediate stage in the model’s development to check for inconsistencies. It was also necessary for groups to collaborate where grid-lines passed through buildings, but the difficulty of accurate matching between one grid-square and the next was mitigated by leaving a gap of 10 mm.

Sources

The initial sources of information for the model were the Ordnance Survey Maps of 1897 and 1903. The use of two editions immediately highlights the problem of a changing situation, for even if there had been a map published in 1900 it would have been out of date, having taken a year or more to prepare. Inevitably there were places that were cleared sites in 1900, and there were buildings under construction: one of our model squares actually shows one of them scaffolded. Groups with sites in transition soon found out about them, and were usually able to establish from records what was present in 1900. Things that had existed for a number of years before or after the date were usually recorded in some way, but more temporary things proved elusive. The impressive octagon marked on the map as Sanger’s Circus, for example, yielded little, and seems to have been extremely short-lived.

Some buildings present in 1900 are of course there still and could be photographed or surveyed in place, but the extent of survival varied greatly from one grid-square to the next. Some parts of the city had remained relatively stable, but others – notably sites of industry, slum housing and post-war ring-road development – had changed out of recognition. One group found only a single pub still intact on their site. In dealing with such areas, careful research was needed to establish the three-dimensional form of the fabric, and here the collections in the City Archive and Local Studies Centre proved essential. Ordnance Survey maps give accurate plot outlines and ground heights, but no information on the number of storeys or the roof-forms, while courts and light-wells are sometimes also missing. Much valuable information could be gathered from period photographs, but the unexpected major source was fire insurance plans. These not only noted the number of storeys and locations of small internal courts, but even details such as rooflights.

Information and discoveries

The physical model was the focus of the research, but the student groups were also asked to provide other kinds of information. They were asked to account for the presence, shape and orientation of every street within their square, and this meant looking at earlier maps to trace the growth-pattern. In some cases it was relatively easy, as for example with the substantial grid-planned layout in the south of the city, which was designed by James Paine in 1770 and laid out between 1788 and 1805. Plans in the archive show not only every detail of the layout, but even the earlier field boundaries. With such information it is possible to explain the development of nearly everything in Sheffield since the mid 18th century, for the first reasonably accurate map by Gosling dates from 1736. From the 1770s onward there are detailed and well-surveyed maps made by the local firm of John Fairbank, which are highly reliable. Much more difficult is the earlier development, which started with the Norman Castle built on a natural prominence between the rivers Don and Sheaf. The market developed outside its gates and the parish church that was to become the current cathedral stood on the hill. The river crossing at Lady’s Bridge was clearly important and the two other major roads leading to the market place – modern Snig Hill and Fargate – obviously played a major role. Some aspects of the town’s morphology offer suggestive hints for possible early wall lines and even a plausible medieval grid, but the evidence is too sparse to support any definite conclusions.

The student groups were also asked systematically to chart the uses of the buildings in 1900, and here contemporary directories were the major source. Such data allowed a consistent series of colour coded plans to be drawn showing uses across the city, and it was immediately obvious that the different squares had very different characters. Some were devoted entirely to industry or working-class housing, but in most of the central area uses were mixed, though in differing proportions. The area around the original markets had by 1900 become the site for the most prominent department stores and the densest collection of inns and hotels, while up the hill towards the Cathedral was an area of legal and commercial offices, and nonconformist chapels. The most memorable Georgian square in Sheffield, Paradise Square, also lay in this area. It was built at the edge of the city, and more sporadically than its form suggests. We were surprised to discover that it had been the main venue for political meetings and the site of sermons by John Wesley. Set on the side of the hill with a central first floor balcony ideally placed as a pulpit, it formed a natural arena.

Moving off from the market in another direction, commerce soon gave way to industry, which even as late as 1900 was located surprisingly close to the centre. The boundary between the two was sometimes marked by showrooms fronting industrial operations, notably the prominent premises of Mappin & Webb, a firm that originated in Sheffield. Moving towards the edges, the students discovered the less salubrious parts of the 19th century city: the enormous shambles beside the river where animals were slaughtered, and the knacker’s yard for recycling worn-out horses, placed cheek by jowl between saw mill and brewery. Illuminated by knowledge of all these uses, the model conveys the impression of a dense city teeming with activity. Spatially the city of that time was organised in a clear hierarchical manner, with major streets giving way to minor, these leading in turn to alleyways and back courts. The pressure for maximal land-use conflicted with the requirement for day-lighting to produce a complex and irregular built pattern of yards and light-wells, a use seemingly being given to every square foot.

Detailed and broader understandings

In addition to the work outlined above, each student within a group was asked to select a building from the grid-square in question and to examine it in detail. In some cases these could be unique buildings of declared architectural significance, such as the Cathedral and the Cutlers’ Hall, but students were equally given the option of looking at an ordinary building as example of a type. Not only are back-to-back houses of a particular period very standardised, but also industrial buildings such as blast-furnaces, and workshops conditioned by daylighting and shaft power transmission. The variety of forms of worship can be seen in the many chapels and Sunday-schools, while the appearance of board schools marks the (in 1900) still recent advent of general education, rigidly divided between boys and girls on a symmetrical plan.

The project was accompanied by lectures and discussions, and one of the topics explored was the nature of building types, and whether they should be classified on a formal, functional or technological basis. We stressed that the language of building types is significant in giving a city coherence both in terms of the repetition that establishes a type and the contrast that differentiates it from another. A further task for the students was to identify the equivalent of their chosen building today, and to pinpoint its location in the modern city. With the later expansion and loosening of density occasioned by motorised transport, many are located in relative isolation and more towards the periphery.

Materializing Sheffield

The final assembly of the model was a dramatic occasion revealing a city none of us had ever seen before, and its riches emerged even more strikingly as the groups presented their detailed findings in turn. We were all struck by the way certain areas of the city had been wholly transformed and by the extraordinary damage inflicted by post-war road schemes. Also fascinating were the many layers of construction serially imposed on the original site of development – the area of the Castle – whose presence today is almost indiscernible although some foundations remain. The grid system of working, initially imposed to divide the work between groups, proved an unexpectedly fruitful analytical tool. A piece of city 200 metres square is large enough to have two or three streets and a character of its own, yet small enough to allow a convincing grasp of the life lived. The possibility of switching from the scale of the city as a whole to that of the grid-square and back again allows an appreciation both of part and whole.

Sheffield is not a beautiful city, and it is surprisingly devoid of pre-modern monuments by nationally known architects, perhaps because of the small scale of its early industry. The tool and cutlery businesses for which it is known grew because of the water power from the steep slopes of the Pennines, the fuel and ore, and the local millstone grit which served for grindstones. The tool and cutlery activities engendered that expertise in steel – particularly Huntsman’s crucible process – that made Sheffield world-famous, but poor communications before the early 19th century meant that its products had to be portable and of relatively high value. It was the steel expertise rather than geographical factors that brought in heavy industry, for by the mid 19th century local ore had been replaced by imported, while water power had given way to steam. The making of large objects such as plate feet thick for battleships could only occur after the arrival of the railways to carry them away. Sheffield’s wealth therefore came late, but even its best display, the Town Hall of 1890-97, is modest in relation to those of Leeds and Manchester. Cutler’s Hall, a building of great local and social significance, started at a modest scale and proceeded back into its deep site by piecemeal extension. It is an architectural oddity rather than an obvious focus of pride.

If the lack of architectural masterpieces prevent Sheffield being ‘worth a visit’ in Michelin Guide terms, it proved an advantage for our study, turning attention back towards the ordinary and the typical. This is needed, for architectural history started in connoisseurship, with the object extracted from its context, and could only engage a few special cases. A project such as Pevsner’s Buildings of England would have been swamped if it tried to do more: hence his now untenable remarks about bicycle sheds, cathedrals and the intention of aesthetic appeal. But if one is trying to understand the nature of places and the forms taken by society, the typical is more telling than the exceptional, while the personal creativity of the architect may be an irrelevance and a distraction. In 1900, in any case, the professional title ‘architect’ was not yet protected, training was in its infancy, and few buildings involved their skills. The new more socially based view of history that has taken over in the last twenty years would suggest an emphasis on ‘society and its buildings’ rather than the individual hero’s oeuvre. Sheffield, with its mixture of commerce, administration and industry, and its rich texture of contrasting types, lends itself well to this approach. Its relatively late growth from a small medieval core also means that it is relatively rich in evidence and much of its story can be reliably established.

Education and beyond

As an educational vehicle the Sheffield urban study project teaches students some social and architectural history as well as how to use maps and archives. More fundamentally, exposure to the evidence of the relationship between social forms and architectural forms should make them more socially conscious as designers. Although some initially regarded the study as a distraction from the more essential activity of design, nearly all seemed by the end to acknowledge the value of their achievement and many were astonished by the sheer scope of ninety-five combined contributions. Never before to our knowledge had the city been looked at in this way, and never had the archive material been assembled in such form. Being able to locate the positions of photographs from Local Studies within the model, for example, gives them a fresh significance. The generous collaboration of both the City Archive and the Local Studies Library , run respectively by Ruth Harman and Doug Hindmarsh, was essential. Both went out of their way to offer training sessions in the use of their material and put up with an onslaught of enquiries that stretched their services to the limit. Anyone contemplating a similar study elsewhere should certainly approach their local Archive early and organise their visits carefully.

Interest from Janet Barnes, then director of the City Museums , resulted in an exhibition being built around our model, which took place in the year 2000. Since then the model has been retained within the school for reference. In addition, via AHRB funded research projects we explored ways of recording the data electronically, and set up the SUCoD web-site , in order to relate the model directly to the modern electronic survey and to make it more easily retrievable and convertible. This threw up a number of methodological issues, particularly questions of how to select a given part of the information and move on to an adjacent part without the process being too long and cumbersome. Also it became evident that the information needed to be more precise and more definitively categorised than our paper files, which could include, for example, handwritten notes, photographs, tapes of interviews, photocopies of archive material, and other such ‘grey’ material which defied categorisation or remained of marginal relevance. The computer tends to force you to make decisions: to divide and categorise, to transform your information into standard form. Its most seductive promise is the flying visual visit to the city at will, with the added possibility that it be chronologically layered so that you can move in time as well as space. This, however, requires enormous data storage and computing power, and involves endless progamming, and can remain slow and cumbersome. More immediately useful in our experience are some less dramatic techniques, such as the ability to make stacks of colour-coded maps with different sets of information and to flip at will electronically from one to another, or the ability to make data simultaneously searchable in a multitude of ways.

In the long-term we hope to be able to make the historical information available for any site in a flexible form. The working basis is a box-file of paper for every grid-square, which is probably the most practical way of assembling data initially, but we are developing ways to recreate this in electronic form, not only to ease the access and storage problems, but to make it searchable in a diversity of ways.

The Model

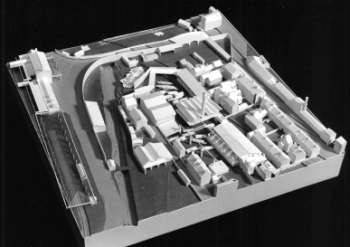

A5 West Bar and Furnace Hill, leading up to Scotland Street. Though of mixed commercial and residential use by this time, this was an important early industrial area and the site of Benjamin Huntsman’s invention of the crucible process.

A5 from above.

A5 from SE.

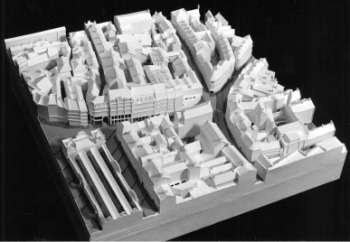

B2 from above.

B2 The present centre of the city with the Town Hall 1893 and St. Paul’s Church to the south of it, Fargate to north. St. Paul’s is the site of the recently reconstructed Peace Gardens.

B2 from NE.

B2 from NW.

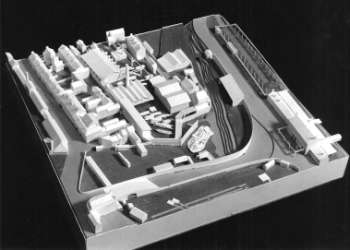

C1 from above.

C1 Turning point in the city geometry where the grid imposed by James Paine in the 18th century meets older fabric to north. Although initially planned as an estate of gentlemen’s houses, it was finally built as an area of small workshops and factories with residences attached. This part of the city was altered beyond recognition by the imposition of Arundel Gate, the inner ring road.

C1 from NW.

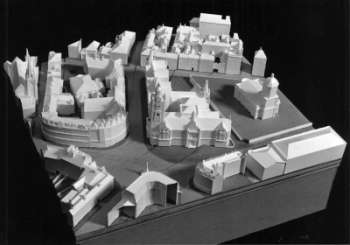

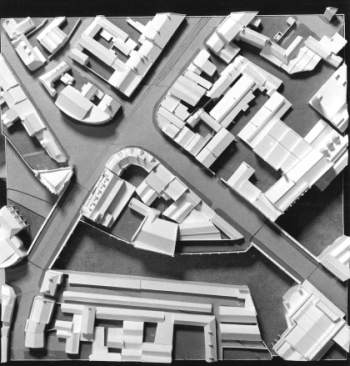

C4 from above.

C4 The original market place, with the two original roads High Street arising from the south-west, and Snig Hill departing to the north west. The original market square had long been filled with buildings, the main market being contained at this stage within the market hall in the south-east corner. The tall block on the west side of the market place is Cockaynes department store.

C4 from E.

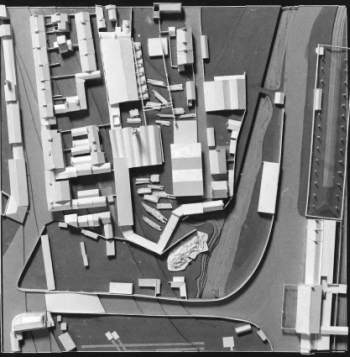

D1 from above.

D1 Sawmill complex in the Sheaf Valley, with the river and railway on the east side. On the west side is workers housing, with a knacker’s yard behind.

D1 from NE.

D1 from SW.

D5 from above.

D5 Lady’s Bridge (south west corner) and the bend in the river Don. The site along the south edge was once occupied by the castle, the starting-point for Sheffield, but by this time was the Shambles, where meat was slaughtered. The river Sheaf had largely been covered over, but its meeting with the Don is still visible to the south east.

D5 from E.

D5 from NE.

D5 from NW.

D5 from SW.

All photos of the model are by Peter Lathey of the University of Sheffield

Change, memory and renewal

The view of Sheffield attained with the study makes it seem a richer and more interesting place, though tinged with sadness that so much of interest has been erased. We noticed that the city has not yet awoken to the world-wide significance of its early industrial history, while the visible remains of heavy industry are still disappearing fast. Industrial sites tend to be large, their fabric worn out, dangerous, and polluted by the time they are abandoned. It is difficult to preserve them or to find new uses. Yet the total erasure of site after site, often destroying the street pattern as well, leaving areas looking like a wartime no-man’s-land until colonised by some new use, seems unnecessarily drastic and unimaginative. Landscape architects like Peter Latz in Germany have shown how such sites can at least be transformed gradually and maintained during the transition, so that some memory of previous use is preserved and the area is left less of a desert. If time is taken over the redevelopment, thought given to how the old patterns might be incorporated, then the new development can be more located and less selfish.

The great question begged by our urban study is how as a designer one should respond to the memory of a site and the geometrical traces which it carries. Although there may be regret at what has been lost, the fact that the form of a city meshes with the life that is lived is inescapable, and as life moves on, the direct and unabridged recreation of past forms is futile and misleading. The decision to demolish and to wipe the slate clean may thus often be justified, but it should not be done in ignorance. Buildings are important bearers of our common memory, and the loss of too many will produce public amnesia, which can be no less tragic than individual amnesia. On the other hand we can be too constrained and limited by the forms of the past and the habits implicitly carried by them. The contempt for things Victorian in the 1960s and the easy destruction which followed reflected precisely the Victorians’ success at consolidating social institutions in buildings and our need to free ourselves from it. But one can free oneself too much: what is needed surely is a balance between the memory of past forms and current needs. There are many inspired examples of architecture that strike this balance magnificently, and are no less innovative for it. See, for example, the work of Swedish architect Erik Gunnar Asplund (see also Blundell Jones 2006)1 or Germany’s Gottfried Böhm . What such examples have in common is a uniqueness of relationship to place and site which roots them and gives them local meaning. At a time when building materials, design fashions and typologies are increasingly generalised and international, with the same kind of ‘Nowheresville’ of architectural objects and landscaped voids springing up around every city, a uniqueness of relationship to site and place is urgently needed. It is something well-educated architects could offer as their particular and special expertise.

References

Blundell Jones, P. 2006 Gunnar Asplund, London: Phaidon

Blundell Jones P., Williams A. and Lintonbon J. ‘The Sheffield Urban Study Project’ in Architectural Research Quarterly, Vol.3, no. 3: 1999, pp 235-244.

- Asplund example is the Gothenburg Law Courts Extension, 1913-37, covered in the Phaidon monograph on pages 31-34, 87-95 and 176-186 (three chronological phases) It is also discussed in Peter Blundell Jones Modern Architecture Through Case Studies Architectural Press Oxford 2002 chapter 11, pages 161-176.