Some Burgundian manuscripts of Froissart’s Chroniques, with particular emphasis on British Library Ms Harley 4379–80By Katariina NäräPlease cite as: Katariina Närä, ‘Some Burgundian manuscripts of Froissart’s Chroniques, with particular emphasis on British Library Ms Harley 4379-80’, in The Online Froissart, ed. by Peter Ainsworth and Godfried Croenen, v. 1.5 (Sheffield: HRIOnline, 2013), http://www.dhi.ac.uk/onlinefroissart/apparatus.jsp?type=intros&intro=f.intros.KN-Burgundian, first published in v. 1.0 (2010).

Jean Froissart (c. 1337–c. 1404), the travelling chronicler-poet of Valenciennes, is often described as the ‘chronicler of chivalry’ on account of the meticulous descriptions of medieval warfare and chivalric glory in his prose Chroniques. Froissart’s Chroniques are an immense work, encompassing events in England, France, Spain and the Low Countries from 1325 to 1400. They therefore cover a large area of Western Europe during the greater part of one of the most violent and eventful centuries of its history; the period known to modern scholars as the Hundred Years’ War. The Chroniques are divided into four books: Book I relates events from 1325 to 1378, Book II from 1379 to 1385 and Book III from 1385 to 1389; Book IV, finally, starts with the ceremonial entry of queen Isabella of France into Paris in 1389 and ends with the death of king Richard II of England in 1400. The survival of well over 100 manuscripts (to date) of Froissart’s great historical work is a clear indication of his popularity; it seems he was something of a bestseller already in his own lifetime. Many of these manuscripts are beautifully illuminated with tens, even hundreds, of hand-painted miniatures and border decorations, often reflecting the owner’s A-list status in the society of the time. Manuscript illumination, an essentially medieval art form, had flourished in the rich Parisian courts during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, despite ongoing warfare and political conflict. Aristocratic and royal patronage had enabled the production of masterpieces such as the Très Riches Heures of John, duke of Berry, and of wonderfully illustrated copies of Froissart’s Chroniques, covering Books I to III. But as political power started to shift away from Paris, due to king Charles VI’s recurring bouts of insanity (reigned 1380–1422), and the consequential regency of his uncles the dukes of Berry and Burgundy, this phenomenon was paralleled in the arts, and the Burgundian Low Countries became a new and flourishing centre for the production of secular vernacular texts. Mercantile prosperity had created great wealth in Flanders, and this wealth, taxed ferociously by its rulers, especially the Valois dukes of Burgundy, facilitated the rise of the ‘Grand Duchy of the West’. The Valois dukes of Burgundy, wealthy rulers of Flanders whose territories included large parts of present-day Belgium and eastern France, had a passion for the arts and especially for illustrated books, that was inspired by royal bibliophiles in France from king Charles V (reigned 1364–1380) onwards. The Valois first duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold (duke 1363–1404), had begun employing artists as part of his retinue whilst still residing in France, following the example of his brother Charles V by becoming an avid collector, sponsor and patron of the arts. The succeeding Burgundian dukes maintained this tradition, and during the great period of political stability, peace and prosperity in the Low Countries which developed in the second half of the fifteenth century, the Burgundian dukes found a virtually inexhaustible supply of artists of the highest quality, the most famous of them being Philip the Good’s court artist Jan van Eyck (Philip the Good was duke 1419–1467). The Burgundian dukes encouraged book production in Flanders and the surrounding areas, attracting commercial and professional artisans from far and wide to satisfy the court’s demand for extravagant and luxurious manuscripts. The Burgundian ducal library, about a quarter of which still survives today in the Royal Library at Brussels, was one of the finest established up to that time. By the time of Philip the Good’s death in 1467, the library contained roughly 867 books and was certainly one of the richest in Europe. Philip the Good’s son, Charles the Bold, the last Valois duke of Burgundy (duke 1467–1477), spent substantial sums on illuminating many of the books his father had originally commissioned but left incomplete, and also commissioned books of his own. The rarest and most expensive products were reserved for the dukes, and their deluxe manuscripts were illuminated by the greatest of painters, since these princes, more than most European rulers, made use of artistic patronage to enhance their public image and to distinguish themselves from the lesser nobility and of course from ordinary people. Burgundian nobles and courtiers desired to emulate the symbols of this princely splendour in order to enhance their own status, and, consequently, they also commissioned manuscripts, rendering themselves ‘visible’ through the inclusion, often on the presentation page of the manuscript, of their coat of arms and motto. Among the leading patrons of this era were many of Charles the Bold’s own family members, courtiers and allies: Anthony of Burgundy (his illegitimate half-brother), Louis of Gruuthuse, governor of Holland and a frequent intermediary between England and Burgundy in political and cultural interplay, and king Edward IV of England, Charles the Bold’s brother-in-law through his third wife Margaret of York. Thus it is not surprising that some of the most splendid manuscripts of Froissart’s Chroniques, and the only complete sets comprising all four Books (and no longer just Books I-III), were produced in Flanders in the latter part of the fifteenth century; in fact, it seems that the Chroniques were something of a fashion item up to the early sixteenth century, especially in and around the ducal court of Burgundy. What made Froissart’s text so attractive? History was certainly of great interest to the Burgundian élite: the ducal library contained all the standard classical texts and their vernacular versions, and Philip the Good was particularly interested in the legends of Troy. Charles the Bold enjoyed listening to readings of history, especially of ancient Rome, and many of his courtiers commissioned historical and instructional texts, most often in French. And Froissart did not write just any old history, but recorded the aristocratic way of life, and therefore the deeds of men of rank and title, some of whom were closely related to members of the Burgundian ruling class. His work was also instructional: it includes examples and stories concerning various rulers and heads of state able to advise a young lord as to how, or how not, to govern his subjects. Also to be found in their pages are evocations of the code of conduct expected of a knight, whether in tournament or actual battle, and minute details of coats of arms seen in banners on the field of battle, or decorating ceremonial progressions. It is no surprise, therefore, that Froissart’s lively account of the history of the nobility of the turbulent fourteenth century, and his descriptions of battles, crusades and tournaments listing individuals and their merits, should be something of a bestseller, and found on the bookshelves of many fashionable, well-off noblemen. One such nobleman was, as we have seen, Anthony of Burgundy (1421–1504), known as the Great Bastard of Burgundy, an illegitimate son of duke Philip the Good, and half-brother to and courtier of Charles the Bold. In addition to commissioning many other splendid books, Anthony was the patron responsible for commissioning the most famous of Froissart’s Chroniques manuscripts: the so-called Breslau manuscript.1 Executed in the workshop of David Aubert in Bruges, this luxurious set comprising all four Books contains 223 images with accompanying border decorations. The volume containing the Book IV text, ms. Rehdiger 4, is dated 1468, and the arms and motto of Anthony of Burgundy frequently decorate the borders of the manuscript.2 After the death of Anthony this magnificent manuscript set passed to his son Adolphe of Burgundy, lord of La Vere and Beveren. In the second half of the sixteenth century, the set was in the possession of Thomas Rehdiger, a Silesian humanist who bequeathed it to the municipal library he had founded in Breslau. During World War II the four volumes of the manuscript were moved to Berlin, where they still reside today. The style of miniatures and decoration varies considerably from one volume to the next, indicating several stages in the execution of the set. The miniatures of Book I are mostly attributed to the workshop of Loyset Liédet, whereas the decoration of Book IV has been connected with various artists such as Liévin van Lathem, Philippe de Mazerolles and the Master of the Golden Fleece.3

Flemish illuminated manuscripts were not meant only for local consumption, but were sought after internationally. English patronage had taken root early on, but a close political and dynastic alliance between England and Burgundy during the reign of Edward IV, culminating in the marriage of Charles the Bold to Margaret of York in 1468, and further cemented by Edward’s stay in Burgundy during his exile between 1470 and 1471, enabled the English king and his courtiers to acquire many Flemish manuscripts. Edward IV’s court was a cultivated one: surviving books are associated with several of the king’s courtiers, and Flemish illuminated manuscripts were much in demand. Members of what has sometimes been called the ‘Calais group’,4 a small group of art enthusiasts and book-owners associated with Lord Hastings, captain of Calais, which included Thomas Thwaytes, John Donne and James Tyrell amongst others, would have had close dealings with officials from the court of Burgundy, such as bibliophile Louis of Gruuthuse. Louis would have known the latest fashion in books in Burgundy, and which texts were being copied and illustrated in the workshops of the Flemish cities. These English noblemen and officials would also have spent time in Burgundy, which would have further facilitated the commissioning of manuscripts from Flemish workshops. Considering the fashion in the late fifteenth century for owning a copy of Froissart’s Chroniques, it is hardly surprising that copies were produced for this literary circle connected to Edward IV’s court. One luxurious set of manuscripts containing the whole of Froissart’s Chroniques is British Library Royal mss 14 D.ii-vi, executed in Bruges between 1471 and 1483. Thomas Thwaytes, Edward IV’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, was the first owner of this magnificent set; his arms appear on the frontispieces to volumes ii to v. The five-volume manuscript was added to the Royal Library not long after it was commissioned, and there has been some speculation as to whether it was a gift from Thwaytes to Edward IV, or whether it was added to the royal collection after the arrest of its owner for treason in 1494.5 Another full set of the Chroniques seems to have been executed for Edward IV himself: the surviving volumes of this set are British Library mss Royal 18 E I and 18 E II (Books II and IV respectively), and J. Paul Getty Museum ms. Ludwig XIII 7 (Book III); the part containing Book I has been deemed lost. These manuscripts were executed in Bruges ca. 1480-83, and it is possible that the set was presented to Edward IV as a gift from Lord Hastings, since BL ms. 18 E I has a sketch of Hastings’ arms, whereas the royal arms of England appear on the frontispiece of BL ms. 18 E II. Getty ms. Ludwig XIII 7 is the most abundantly illustrated copy of Book III of the Chroniques, with no less than 64 miniatures; Scot McKendrick has recently classified the main artist of this manuscript as the Master of the Getty Froissart, also identifying six other miniaturists at work on this luxurious volume.6

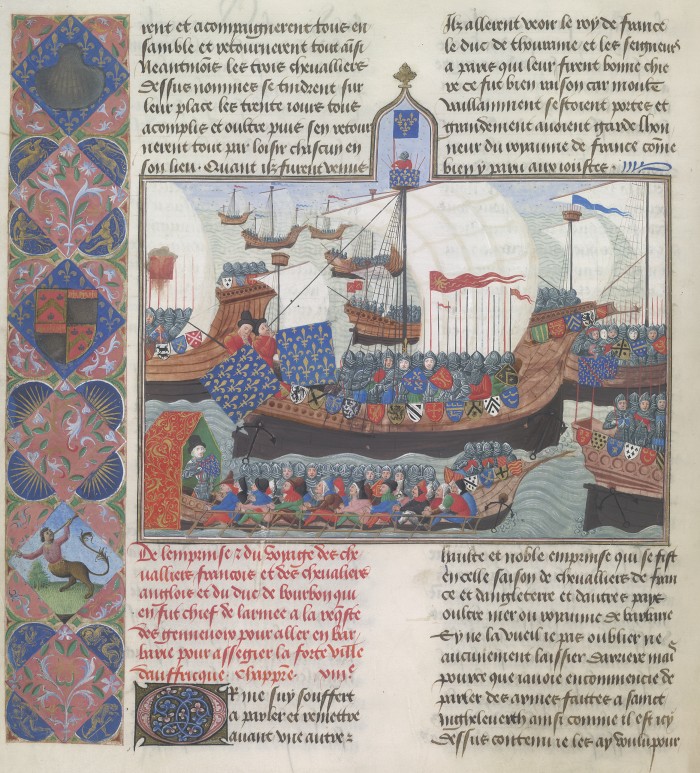

Apart from complete sets of Froissart’s Chroniques, individual manuscripts were also commissioned and executed; one such manuscript is British Library ms. Harley 4379-4380, an important early witness of Book IV of the Chroniques, originally produced as a single codex in Bruges between 1470 and 1472. The recipient of this luxurious book (now bound as two separate volumes) was Philippe de Commynes, lord of Argenton (1447-1511), at this time one of the counsellors and courtiers of bibliophile Charles the Bold. The arms of Commynes, quartered with those of his mother, Marguerite d’Armuyden, appear frequently in the margins of both volumes. It is commonly acknowledged that the presence of the d’Armuyden arms would date the Harley manuscript to no later than 1472, before Commynes left Burgundy, since after this date he changed his allegiance to Louis XI of France, and from then on his arms usually appear alone. There is some evidence in Harley ms. 4380 that some of the shields bearing the arms of Commynes were surmounted by a crown, but the crowns have been scraped out and overpainted (e.g. ms. 4380, fols. 89, 172v). Whether this was due to a change of mind on the part of the artist, or to a change of recipient, is open to conjecture but impossible to establish. There are eighty fully painted miniatures in the two-volume manuscript (29 in 4379 and 51 in 4380), attributed to two artists: the Master of the Harley Froissart and the Master of the Vienna Chroniques d’Angleterre. The miniatures are placed at the beginning of each chapter (only chapters 4 and 7 in ms. 4379 do not have miniatures). Each miniature is framed by a pink and gold bar, and they are invariably accompanied by marginal decorations. Only the frontispiece of the manuscript, Queen Isabella’s ceremonial entry into Paris (ms. 4379, fol. 3), has full border decorations including an inter-columnar foliate border with acanthus leaves, flowers, strawberries and fruits on a gold background, with two hybrids. The other miniatures have partial borders, invariably occupying the outer margin of the page, and most often decorated with a distinctive type of foliate border on white or gold background with hybrids, drolleries, knights and heraldic beasts, even angels. Sometimes the foliate border forms a background for a chain of lozenges, as in ms. 4379, fols. 60v and 160, containing an escutcheon with the arms of Commynes on France ancient (azure, semi of fleurs-de-lys, or), the Coquille St. Jacques similarly on France ancient, and an heraldic beast or hybrid; in between these reoccurring motifs (every other lozenge in the chain of six) one finds lozenges with a stylized floral pattern on a deep rose-coloured background. However, the most unusual border decorations found in mss Harley 4379-4380 are the ‘box’ borders, with three, roughly equal-sized squares, with foliate pattern in between, each containing a lozenge (e.g. ms. 4379, fols. 29v, 36, 83v; ms. 4380, fols. 1, 134). In the lozenges are depicted the arms of Commynes on France ancient, the Coquille St. Jacques also on France ancient, and an heraldic beast. The order of the lozenges varies, as does the heraldic beast. This type of border is French in style and common in earlier illuminated manuscripts, but not usually found in Flemish manuscripts. It is possible that the Paris-trained Master of the Harley Froissart planned and possibly even painted these borders, thinking back to models of manuscript illumination that he would have seen during his training in France. This is, of course, just a hypothesis. Each chapter also opens with a decorated initial; the size of these major initials depends on the size of the miniature (there is usually a three-line initial for one-column miniatures, and a four-line initial for half-page miniatures). Textual breaks in the chapters are marked with a pied-de-mouche (paragraph marker) and pen-flourished initial occupying the height of two lines. Further decoration can be found in the form of line fillers, and Burgundian style cadels and pen-flourishes. The Master of the Harley Froissart, who takes his name from this codex, is responsible for most of the miniatures in mss Harley 4379-4380. He was trained in the old traditions of Parisian illumination and possibly painted the Harley illuminations at an early date in his career, as Scot McKendrick suggests, whereas the Master of the Vienna Chroniques d’Angleterre was an artist from Bruges, named after one of his most extensively illustrated manuscripts.7 McKendrick also notes that as a few of the miniatures are clearly the collaborative work of both artists, ‘it is evident that the two artists worked very closely on the present volume’.8 Examples of this collaboration are e.g. ms. 4380, fol. 149, where the trees and landscape are by the Vienna master, whereas the figures are painted by the Harley master; similarly in ms. 4380, fol. 151, the architecture is by the Vienna master and the figures, once again, by the Harley master. The Master of the Harley Froissart’s delight in lavish heraldic display on banners, standards, and horse trappings has not gone unnoticed in the past, and while it is true that these displays enliven depictions of armies on the march and add splashes of colour to the otherwise pale palette of the artist, they also often link the image to the chapter text. The expedition of the duke of Bourbon to Barbary is a particularly eloquent example: here one finds coats of arms painted on banners and escutcheons, belonging to people whom Froissart mentions as participants in this voyage, such as those of the duke of Bourbon, Philip of Artois, the duke of Bar and, surprisingly, John Beaufort of Lancaster (bastard son of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster).

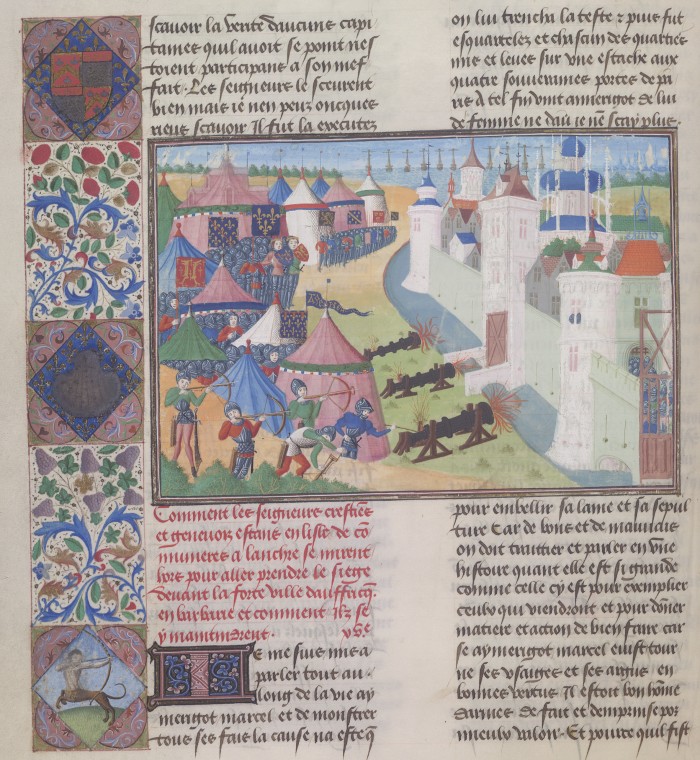

This somewhat conventional setting of ships on the sea to mark the departure of an expeditionary force, the type for which can be found in most of the illustrated manuscripts of Froissart, is transformed into a recollection of a specific voyage led by the king of France’s uncle, the duke of Bourbon, who is portrayed standing on the deck of the main ship and in the middle, as befits his rank as leader of this expedition. He is also depicted in a straight line with the mast that extends all the way to the top of the miniature, and which is also at the exact centre point of the miniature. This type of balanced composition is very much in the style of the Master of the Harley Froissart. Bourbon is shown wearing a helmet crowned with a golden fleur-de-lys, and holding an escutcheon of his arms. To his left stands the duke of Bar, although curiously the artist paints the background of the arms gules (red) whereas it should be azure (blue). There can be no doubt however that the Master of the Harley Froissart is portraying the arms of Bar when one looks at other miniatures in this manuscript where the arms are also present, because apart from the colour, the presentation of the arms is immaculate. Philip of Artois, count of Eu, is depicted on his own ship. He is clearly recognisable as he is standing to the aft of the ship in full armour, protected by a gold and red patterned canopy, and holding an escutcheon of his arms. In addition to these French noblemen, one can just make out a soldier holding an escutcheon with the quartered arms of England and France, crossed with a ‘bend sinister argent’ that would be an acceptable heraldic signifier for a bastard. This could signify the presence of John Beaufort of Lancaster, bastard son of John of Gaunt, as he is mentioned by Froissart in the text. One should also note that two of the shields shown on the side of the main ship carry the arms, respectively, of Flanders and Brabant. Although many of the other arms displayed are probably fanciful, the artist clearly had some knowledge of heraldry, and, most importantly, had a keen interest in heraldic devices, for he took great care in painting them. It is apparent also that the artist is depicting the splendour of France and its ‘grands seigneurs’ present on this expedition, and their status as overlords to the knights and lords of England, Flanders, Brabant, Hainault, Normandy and Brittany, some of whom are listed by Froissart as participants in this voyage. This is further underlined by the artist’s positioning of the insignia of the king of France above all of the other devices within the flamboyant arch which crowns the miniature, done in the style of contemporary Gothic ecclesiastical architecture. In the Book IV text, the long chapter relating the fate of Aimerigot Marcel separates the two chapters that narrate the departure of the French army for Barbary, and the consequent siege of Mahdia. As with the image of the French host at sea, the miniature picturing the siege of Mahdia, or, as Froissart calls the town, ‘Affricque’, the quite conventional setting of a town under siege is turned into a specific event by the artist’s display of heraldic banners.

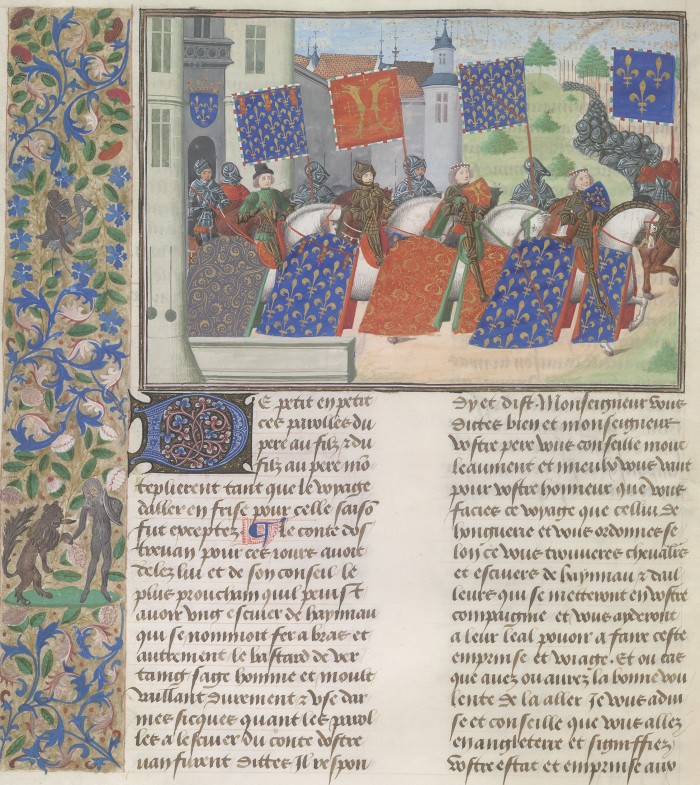

The now familiar arms of France, Bourbon, Artois and Bar are all shown flying above the pavilions that represent the camp of the war host. The banner of the king of France is shown in the middle, slightly higher than the rest, as is entirely appropriate. The duke of Bourbon is depicted standing in the middle of the host, as Froissart intimates (fol. 88b), and although the artist has omitted Philip of Artois from the picture, he has depicted the arms of Artois to the right of Bourbon, just where Froissart places him in the text. The duke of Bar is pictured next to Bourbon, and the banner of Flanders is also present a little further apart. Froissart gives a long list of names of lords and knights present at this siege, but the artist chose to depict only the arms that belonged to the leaders. The host’s fleet of ships is depicted in the background, linking the image not only to the text, but to the earlier miniature also. The miniature that opens chapter 48 (ms. 4380, fol. 58v) represents another departure on an expedition: that of the French to Hungary. As in the earlier images, the familiar arms of France, Bar and Artois dominate the foreground. The city depicted in the background is shown with a crowned escutcheon of the French king’s arms, symbolising the departure from France, whilst Charles VI’s personal colours - red, white and green - frame all the banners. It is difficult to establish whether the Master of the Harley Froissart was familiar with the chapter text, as he pictures the duke of Bourbon as the leader of this expedition instead of the count of Nevers, son of the duke of Burgundy, who was the actual leader of the French on this ill-fated campaign. This is evident not only because of the arms of Bourbon carried by the lord to the right of the miniature, but because he is shown wearing a ducal coronet that one is used to seeing on the heads of the royal uncles and dukes, both English and French, in other miniatures in this manuscript. The figure depicted behind him, the duke of Bar, is wearing an identical coronet, whereas the count of Eu, Philip of Artois, is differentiated in rank since he is shown wearing a hat. It should be noted that the artist portrays Artois wearing an identical hat in the earlier miniature depicting the departure for Barbary; a link is thus created between the two images, as well as with the text.

In addition to the luxurious manuscripts meant for royalty and high nobility, such as the Harley manuscript, cheaper versions of Froissart’s Chroniques were also executed in Burgundian workshops. Alberto Varvaro’s base manuscript for his partial edition of the Book IV text, Brussels Royal Library ms. IV 467, is one such. This manuscript was executed in southern Flanders in 1470, and copied on paper rather than vellum. It has just one large miniature depicting the ceremonial entry of Isabella of Bavaria into Paris. But, according to Varvaro it is the text of these more modest manuscripts that comes closest to Froissart’s original narrative. He also questions whether the integrity of the text itself, as found in at least some exemplars, such as Harley mss 4379-80 and also the Breslau manuscript, was to some extent compromised by the production of these deluxe witnesses, where more emphasis was given to the appearance of the manuscript than to the consistent accuracy of its text. But in reading and collating various chapters from both above-mentioned manuscripts, and from the Brussels manuscript, the differences between readings do not indicate any large-scale corruption that would decisively affect the content of Book IV in the Harley ms., or of its representation of its author’s narrative tone. In fact, it is possible to argue that because of the illuminations, not only is the art-historical value of Harley mss 4379-80 very considerable, but that it also offers us the opportunity - when we compare the text against the miniature for each chapter - to study the perception of historical events, and Froissart’s depiction of them, from an artist’s, patron’s and workshop’s point of view, some seventy years after they took place. Notes1 Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, dépôt Breslau I, ms. Rehdiger 1–4.2 See e.g. fols 156, 229v, 309v and above-mentioned 321v. 3 See Laetitia Le Guay, Les princes de Bourgogne lecteurs de Froissart. Les rapports entre le texte et l’image dans les manuscrits enluminés du livre IV des Chroniques, Documents, études et répertoires publiés par l’Institut de Recherche et d’Histoire des Textes ([Paris / Turnhout]: CNRS Éditions / Brepols, 1998), p. 176; Christiane Van den Bergen-Pantens, ‘Héraldique et bibliophilie: le cas d’Antoine, Grand Bâtard de Bourgogne (1421–1504)’, in Miscellanea Martin Wittek. Album de codicologie et de paléographie offert à Martin Wittek, ed. by Anny Raman and Eugène Manning (Louvain/Paris: Editions Peeters, 1993), pp. 323–54 (p. 333). 4 Anne F. Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs, ‘Choosing a book in late fifteenth-century England and Burgundy’, in England and the Low Countries in the late Middle Ages, ed. by Caroline Barron and Nigel Saul (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1995), pp. 61–98 (p. 80). 5 Le Guay, Les princes de Bourgogne, p. 184; Sutton and Visser-Fuchs, ‘Choosing a Book’, p. 82; J. Backhouse, ‘Founders of the Royal Library: Edward IV and Henry VII as collectors of illuminated manuscripts’, in England in the fifteenth century. Proceedings of the 1986 Harlaxton symposium, ed. by D. Williams (Woodbridge, 1987), pp. 23–41 (p. 30). 6 Thomas Kren and Scot McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe (Los Angeles: Getty Pulications, 2003), p. 286. 7 Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, p. 262–63. For the career of the Master of the Harley Froissart, and for other illuminated manuscripts attributed to him, see Kren and McKendrick, p. 261–62; John Plummer, The Last Flowering: French Painting in Manuscripts (London: Oxford University Press, 1982), pp. 64–65. 8 Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, p. 262. McKendrick also lists two other manuscripts that the two artists collaborated on: a Chroniques d’Angleterre and a copy of Monstrelet’s Chroniques. |