|

|

Besançon

Bibliothèque

municipale

ms. 864

This manuscripts contains 25 miniatures by the Giac Master and has

pen-flourished initials.

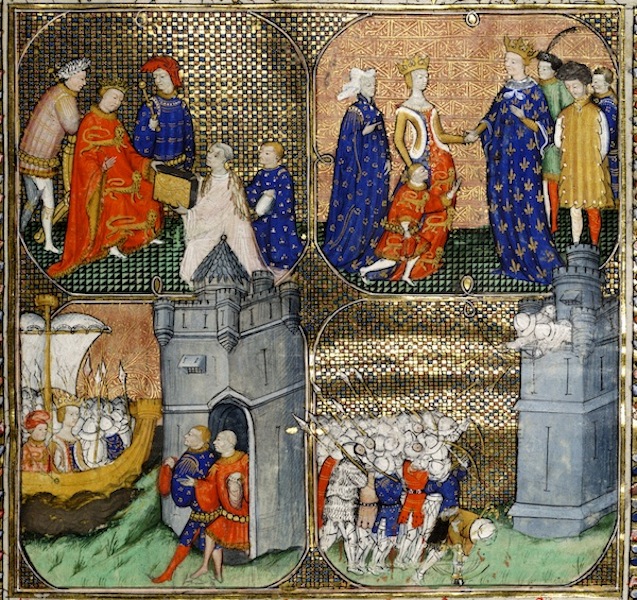

fol. 1r: four-part opening miniature representing the following scenes: - A king of England, most plausibly Richard II,

receives the chronicler who kneels before him, his canon’s almuce (a short fur cape)

around his shoulders, accompanied by a page. The Plantagenet leopards (royal

lions) are shown reversed so that they appear to stare at the chronicler. Two counsellors

stand behind the throne, one of them recognisable as the chancellor on account of his

wand of office. The scene calls to mind Froissart’s final visit to England in 1395, related in Book IV of the Chronicles, during which he met king Richard and presented him with a luxurious bound manuscript book containing his collected love

poetry (though what is represented here is a volume perhaps intended to represent the

Chronicles).

- Charles IV of France, accompanied by courtiers,

welcomes to his court in 1325 queen Isabella of England, his sister, who wears a robe

bearing the arms of France and England dimidiated (divided per

pale, i.e. vertically), and his nephew the future king Edward III. Once again, the English

leopards look towards the French. The young prince, holding his hat in his right hand,

raises the other to greet his uncle of France. A figure standing to Charles’ immediate left is wearing a sleeveless tunic like a tabard, called in French an huque, a

detail found in at least one other Book I manuscript’s presentation page miniature for this scene

(Toulouse Mun. Libr., ms. 511, f. 8).

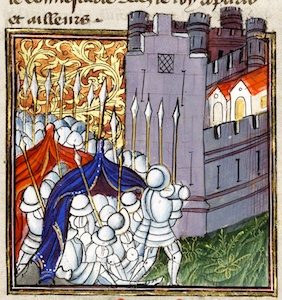

- Queen Isabella,

crowned, and prince Edward, wearing a red hat, accompanied by soldiers of their

expeditionary force in kettle hats and carrying spears for war, make landfall in 1325 outside a

fortified town with crenellated battlements and corner towers. The scene most plausibly depicts

Isabella’s landing at Orwell near Harwich in Essex. Two men in court

costume and carrying their hats step forward from the doorway of a town (possibly Bury

St Edmunds) to greet the queen and her son.

- The

queen of England and her army lay siege to the city of Bristol where her

husband king Edward II has taken refuge along with his counsellors and favourites, the

Despensers.

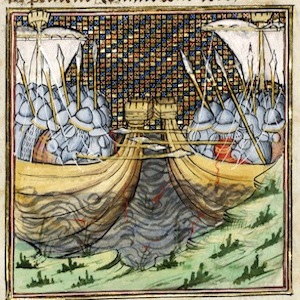

fol. 34v: Battle of Cadzand (1337), Giac Master. The battle of Cadsand (November 1337) was little more than a

skirmish between an English force commanded by Sir Walter Manny (who had

succeeded in taking this small, marshy island and its Franco-Flemish garrison) and a French force

sent from Sluys under the command of Guy of Flanders. Even

so, a good many French were killed, and a few English also. The

Giac Master’s composition contrasts the double rows of oblique lances of the

French on their galleys to the left, with the more aggressive, bristling ‘hedgehog’

of English lances in the right-hand foreground (echoed by the four lances brandished by the

garrison’s defenders, above). This encounter was the prelude to the rekindling of Edward

III’s ambitions in France.

fol. 46v: The court of Edward III of England (1340), Giac Master. Edward III, surrounded by his counsellors and seated in

majesty on a throne surmounted by a red canopy, wears a robe embroidered with the arms of France and England quarterly, those that he adopted upon

proclaiming himself king of France and England in 1340. The figure in the blue

houppelande and hat to his right is almost certainly Robert, count of Artois, who

had taken refuge in England and was credited by Froissart with

the role of encouraging the English king to reassert his claim to the French crown.

fol. 59r: Giac Master. Battle of Sluys (1340).

Describing the defeat of the French fleet off the Flemish coast to the NW of Bruges near the Zwin estuary, on 24 June 1340, Froissart writes:

‘The battle of which I speak was extremely grim and terrible, for battles at sea are more

severe than those on land; for at sea there is no opportunity for retreat or flight, but men must sell

themselves dearly and fight hard, and await what must befall, and each and every man must look

to his own courage and prowess’ (Book I, ed. Diller-Ainsworth, p. 293; tr. PFA). The

Giac Master’s composition shows us two galleys confronting one another near

the shore; the reality of the matter was that the French fleet comprised no fewer

than 200 vessels.

fol. 72v: Giac Master, Funeral cortège of John III, duke

of Brittany (1341). On 30 April 1341, John III, duke of Brittany died at Caen without leaving an heir. His niece, Joan of Penthièvre, and his

half-brother John of Montfort, would henceforward contest the right to succeed to the duchy, in what became known as the War of the Breton Succession. In a compact but

harmonious composition, the Giac Master paints the funeral procession as it

disappears through an archway into a fortified town; the bier, under a pall embroidered with

ermine (for ‘Brittany’), is mounted on a wagon pulled by two horses and

accompanied by an escort of knights and men-at-arms with lances held aloft – but sloped as they

enter the gateway.

fol. 91r: Giac Master. Combat between an English force and

a French one led by Louis of Spain (1342). Louis de la Cerda, known

as Louis of Spain, was created admiral of France in 1341 and took part in the

War of the Breton Succession in support of the pro-French Charles of Blois. French and English (the latter summoned to her assistance by

the countess of Montfort) are recognisable by their respective banners in this vigorous

composition by the Giac Master illustrating the battle of Quimperlé. Blood is flowing freely on the French side, the bodies piling up.

fol. 112r: Giac Master. The Siege of Auberoche (Périgord) by the count of Lille (1345). On a bluff high above its besiegers

stands the fortress of Auberoche with its roof and corner turrets covered with blue tiles,

towering above and beyond the limits of the miniature’s frame. The fortress was

besieged in October 1345 by the troops of count Bertrand de Lille-Jourdain, arrayed

here in kettle hats and ‘white armour’ (plates) comprising breastplate or cuirass, skirt with tassets,

pauldrons (protecting the shoulders), plate rondels (over the elbows), plate gauntlets, poleyns (for

the knees), greaves (leg defenses) and sabatons for the feet. Two artillerymen kneel at their

bombards, which are encircled with iron bands and mounted on wooden limbers, firing large stone

balls towards the fortress walls. The damage these could do is described in another

passage from the Chronicles: ‘So four large siege engines were sent for from Toulouse, and they had them brought hither on carts and raised in front of the fortress.

And the French conducted their assault with these only, the engines hurling heavy

stone projectiles at and into the castle. This dismayed the defenders more than anything else;

within six days the projectiles had battered down most of the upper parts of the towers, so that

neither the knights nor the castle’s garrison dared to stay put, save in vaulted chambers

underground’.

fol. 130r: Giac Master. The English

disembark in Normandy (1346). King Edward III of England arrived

at Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue in the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy on 12 July 1346; thus began a campaign which would reach its climax in his victory

at Crécy and the subsequent taking of Calais. The Giac

Master evokes Edward III’s arrival in Normandy by

depicting the sack of Caen and the massacre of around 5,000 of its citizens on

26 July 1346. The dead lie, slain by soldiery equipped with pole arms; even a church has been

torched by the marauding English.

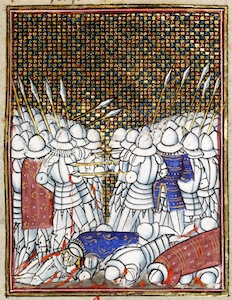

fol. 135r: Giac Master. Battle of the Ford at La

Blanchetaque on the Somme (1346). In August 1346, at the ford of La Blanchetaque near Abbeville, the only viable means of crossing the Somme at low tide, the English – only recently disembarked in France – attempted to force their way over a river crossing defended by French troops led

by Godemar du Fay. The English had to fight numerous

one-to-one engagements in the river itself, but Edward’s men emerged

victorious, the French infantry suffering heavy losses. A rock in the background suggests the

escarpment of the river bank.

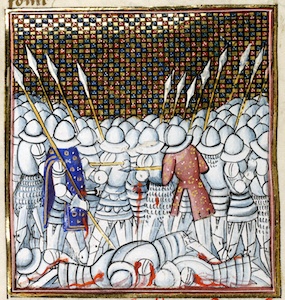

fol. 138r: Giac Master. Battle of Crécy

(1346). On 26 August 1346, the French, hard on the heels of Edward

III’s army, finally forced their enemy into a pitched battle at Crécy-en-Ponthieu, but suffered a bitter defeat. The Giac Master’s composition is rather

stiff and lifeless when compared to other contemporary manuscript miniatures depicting the

famous battle. The crowned figure lying in a heap of bloodied corpses in the left

foreground is John, blind king of Bohemia, who had himself carried into the fray on his

own horse, attached to those of his barons by leather straps.

fol. 145v: Giac Master. Philippa of Hainault, queen of

England, at the Battle of Neville’s Cross (1346). On 17 October 1346 a

Scottish army commanded by William Douglas surprised an English force

encamped near Durham. England found herself squeezed

between the French across the Channel on the one hand, and David II

of Scotland, ally of the French, on the other. The chapter introduced by

this miniature describes how, in the absence abroad of Edward III, ‘The queen of England, whose desire it was to defend her country, came as far as Newcastle upon Tyne, and there awaited her people’. The battle between the troops

mustered by queen Philippa and those of David II took place at Neville’s Cross on 17 October 1346. In the miniature, the battle is being fought

on foot. Below the interplay of lances, the Scots – to the right – pile up in a

bloodied heap; their king was captured at the end of this battle. The warrior queen, in her crown and dimidiated heraldic robe marshalling the arms of France and England points an energetic finger in the direction of her

Scottish adversaries.

fol. 150v: Giac Master. Charles of Blois

captured at La Roche-Derrien (1347). In May 1347, in the course of the War of

the Breton Succession, Charles of Blois laid siege to La Roche-Derrien, a stronghold occupied by the supporters of his Montfortist rival and their

English allies. The castle with its blue-tiled roof and multiple turrets rises out of the picture frame

above the fray beneath, showing the troops of Sir Thomas Dagworth repulsing the

assault by the French. Charles of Blois was duly captured. The

Giac Master is sufficiently interested in details to include here, in the foreground,

the small hinges securing Sir Thomas Dagworth’s cuirass at the back (he is recognisable

by his helm).

fol. 159v: Giac Master. Death of Philip VI of Valois,

king of France (1350). The royal bier, draped with a blue cloth powdered with gold

fleurs-de-lys and flanked by four tall candlesticks, is represented in miniatures found in several

manuscripts of Froissart’s Chronicles. The mourners in their heavy back robes

are reminiscent of the stone weepers, almost exactly contemporaneous with this manuscript

painting, which still decorate the tomb of duke Philip the Bold of Burgundy, in Dijon.

fol. 172r: Giac Master. Battle of Poitiers

at Maupertuis (1356). John the Good’s attempts at putting an

end to chevauchées into French territory by the prince of Wales and Aquitaine, Edward of

Woodstock, eldest son of Edward III, culminated with the capture of the

French king at the battle of Poitiers (19 September 1356). John’s

son Philip, although subsequently interned along with his father, acquired the

sobriquet ‘the Bold’ as a result of his conduct on the battlefield. The Giac Master

shows the king of France, his bascinet surmounted by a golden crown with fleurs-de-lys,

and with visor raised. To the left, seizing hold of him, is Edward, prince of Wales and

Aquitaine, recognisable by his jupon embroidered with the arms of France

and England. This miniature appears to espouse an anglocentric viewpoint! The

first person to take hold of the French king was, in fact, Denis of Morbeke, a knight

from the Artois fighting under the prince of Wales’ banner. The English would go on to demand a ransom for king John of no less than 350,000 écus.

fol. 181r: Giac Master. Death of Godfrey of

Harcourt (1356). The defeat of Godfrey de Harcourt, a Norman knight who

supported Edward III’s cause, in the vicinity of his fief at Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte, is evoked here in a spare but dramatic composition.

Numerous figures are energetically engaged with one another both on foot and on horseback. One

notes once again the hinges closing the back of the cuirass of the figure in the foreground.

fol. 235r: Giac Master. The Captivity of John II the

Good of France in London (1360). Here, the Giac Master portrays Edward III of England and his royal French prisoner John

II, both in armorial robes and accompanied by their respective counsellors. Treated with

great courtesy, king John even appears to be arguing his case in this scene. The two

kings are shown as equal in rank in terms of the medieval pictorial conventions used in this

composition.

fol. 243v: Giac Master. Battle of Cocherel

(1364). At Cocherel, on 16 May 1364, just three days after the coronation of Charles V as king of France, his army, commanded by Bertrand Du Guesclin, secured a resounding victory which augured well for the new

reign, over the army of Charles the Bad, count of Evreux and king of Navarre, led by

Jean de Grailly, captal (lord) of Buch, and his English allies. The Navarrese, hemmed in against a fortified position on a hillside, were put at a disadavantage. The

hill is shown by the illuminator. The Giac Master has gone for a foreshortened,

dramatic portrayal of the battle, with the dead piling up in the foreground.

fol. 250v: Giac Master. Battle of Auray

(1364). Auray would prove to be the final battle of the War of the Breton

Succession between John IV of Montfort, supported by the English under the command of Sir John Chandos, and Charles of Blois, whose vanguard was entrusted to the great French captain Bertrand Du Guesclin. Charles was killed by a lance thrust, whilst Du Guesclin,

having broken his weapon, was obliged to surrender to Chandos, one of the great

English heroes of Froissart’s Chronicles. The Giac Master

shows us the capture of Du Guesclin by the Anglo-Bretons; he is easily

recognisable on account of his emblasoned surcoat: argent, a double-headed eagle displayed sable,

beaked, armed and langued gules, overall a bend gules. Having obtained a ransom of 100,000

francs, Chandos soon let Du Guesclin go.

fol. 277v: Giac Master. Battle of Nájera

(1367). The battle of Nájera near Navarrete (3 April 1367) won by Sir John

Chandos, the Captal of Buch, English marshal Steven Cosington

and Poitevin marshal Guichard d’Angle, was a crushing defeat by the prince of

Wales’ Anglo-Gascon army of the Franco-Castilian force commanded by Du

Guesclin. The Anglo-Gascons chose to fight on foot, wrongfooting Du Guesclin and the Castilian heavy cavalry; the tactic was a great success. The collapse of the

Franco-Castilian formations culminated in the capture of Du Guesclin, his ransom

being set at 100,000 Castilian doblas.

fol. 286v: Giac Master. Having lost the support of the prince of Wales and Aquitaine, Pedro of Castille was captured at the battle of Montiel and handed over to his rival Enrico of Trastámara.

The Giac Master does not conceal the brutality of the fate met by Pedro, assassinated by Enrico of Trastámara on 23 March 1369 in Du Guesclin’s tent, a few days after the battle of Montiel. Enrico’s sword seems to have found a weak point between the plates protecting Pedro’s stomach.

fol. 312r: Giac Master. The siege laid by the soldiers of Louis of Sancerre, marshal of France, to the fortified stronghold of Puirenon used by John Hastings, earl of Pembroke, as a secure place of resort, is

illustrated at a crucial moment: equipped with shovels and picks, French sappers are busy digging

a hole under a corner of the building in order to bring down a stretch of wall. Pembroke was saved in extremis by Sir John Chandos, with whom he had earlier refused

to share command of military operations in the area.

fol. 330r: Giac Master. The city of Limoges goes

over to John, duke of Berry (1370). On 24 August 1370, Jean de Cros, bishop of

Limoges , had the gates of this hitherto pro-English city opened to receive John, duke of Berry. The town’s magistrates are shown offering duke John the keys to the city of Limoges. The duke, who marches at the head

of his army wears an armorial huque of azure, semy of fleurs-de-lys or, within a bordure engrailed,

gules (for ‘Berry’). The consequential English reprisals taken by the prince of Wales on

19 September 1370 are notorious: the city was retaken and almost all of its inhabitants

massacred.

fol. 343v: Giac Master. Combat at sea off the coast near La Rochelle (1372). On 10 June 1372 a fleet commanded by the earl of

Pembroke set sail from Southampton laden with reinforcements destined

for English garrisons in Guyenne (Aquitaine). A Castilian fleet

commanded by Genoese admiral Simone Boccanegra intercepted them off the coast

near La Rochelle, inflicting a resounding defeat. Pembroke was

to die in captivity in Picardy, in 1375. The Giac Master portrays

the battle against the backdrop of a town built on rocks at the edge of the sea: two galleys are

engaged in much the same way as two battalions would close with one another in a land battle.

fol. 358r: Giac Master. Siege of Bécherel

(1372). A group of French soldiers in plate armour and kettle hats set up blue- and red-striped

campaign tents in front of the town of Bécherel in Brittany; the town was

recaptured from the English by Bertrand Du Guesclin after a

twelve-month siege.

fol. 384v: Giac Master. Alliance between the kings of

Navarre and England (1378). Two kings, crowned and wearing fur-lined robes

respectively of deep blue powdered with small flowers, and of vermilion powdered with gold

stars, offer each other their right hand, signifying the conclusion of an alliance. The Giac

Master here depicts an interview which took place at Windsor Castle

in February 1378 between Charles the Bad, count of Evreux and king of Navarre, and

the young king Richard II of England.

|